In conversation with my elder, amina wadud

amina wadud invited me to talk about our explorations of sexual diversity and human dignity— and the ethical question of our time for Muslims everywhere.

I was invited to speak with nonbinary tawhidic ethicist amina wadud in February 2021 as part of their Friends Along The Way video series. In our hour-long conversation, we talked about what we observed in our own explorations of sexual diversity and human dignity, how it is the ethical question of our time for Muslims everywhere, and a quick tour of The Signs In Ourselves: Exploring Queer Muslim Courage, a wellbeing resource available for free thanks to CSBR.

Transcript

aw: I begin as i always begin, in the name of Allah whose grace I seek in this and all other matters. Thank you for joining me for my Friends Along The Way. I want to introduce my friend. Liy Yusof is a Southeast Asian nonbinary writer working in collective learning and memory. After six years documenting within feminist movements, they were inspired to co-create the Signs In Ourselves: Exploring Queer Muslim Courage in 2020, an inclusive Muslim wellbeing resource inspired by Quranic verse 41:53, and 51:20-21 among others. Made possible by the CSBR the Coalition for Sexual and Bodily Rights in Muslim Societies, the publication is available as a free download for personal and collective here: https://dub.sh/TheSignsInOurselves. Liy grew up with spirituality, science, the supernatural and the internet, and maintains over 20 years of searchable notes and journal entries, along with a few houseplants.

Liy: Thank you for inviting me. I imagine this to be a conversation between us, so I also have a few questions for you along the way. I'm very very grateful for this opportunity. Yes, I wrote The Signs In Ourselves and I am really excited to talk about it today, along with a little bit about myself, although this is very new to me in many ways.

aw: I am very happy to make it more conversational. I can jump right in if you don't mind. I am a student of yours, in the time that I spent as your student I realised that ppl who grow up in the digital world, unlike myself who I consider to be an analogue woman in a digital age. They have a mode of operation, language, hermeneutics as it were, and I am an outsider, and I need sometimes to communicate between my location and the facility of the digital world. And I only learned this because of working with you. Because I didn't sound I was speaking as much as a foreign language as I always feel, I always feel outside out of it. Could you tell me some things you have observed in your professional context of searchable notes and journal entries? Tell me something about the way in which this digital age actually shapes what you do, how you identify yourself, and what you aspire to.

Liy: First things first, I have to say that it is completely an inverted experience with what you're saying. Because I feel I have so much to learn from you, I'm also a student of yours. Just as how you say there is a language and hermeneutics that maybe this through this intergenerational friendship you learn a bit more of, what I feel I am so privileged to be able to learn is to learn more about the language of faith in general— something I thought was inaccessible to me as a sexually diverse Muslim. Often told we don't have access to this sort of language. And we don't have many scholars who directly support our dignity. So to hear and learn about the tawhidic paradigm from you was very instructional for me in finding a way to understand a little more about my own self and personality, and the kind of Muslim I wanted to be.

Liy: Your question was after my observations, what have I learned about how the digital age shapes what I do and how I identify. I think what I've learned— if I could summarise the process of not only just writing this book but meeting the people I needed to meet including you to make this book happen— was that I think Muslims really need to change the way that we are having this whole conversation about queer Muslims from the angle of sex and reproductive value, to something around the idea of gender as a part of human biodiversity. And to accept that preserving and respecting biodiversity is a priority that we have to make for our social and planetary survival. So this idea of the digital age if that shaped me at all, is that I had an analogue childhood but the moment the internet came I felt like my library just got much much bigger. I could find out about so much. And I think that's definitely something that's a gift and a curse in this whole age of the digital. This idea of we have access to so much in basically our palm, so much information. What do we want to do with that information? How does it change the conversations that we should be having?

Liy: What else have I observed? I think other Muslims have a lot to learn from sexually diverse Muslims. That is something, that was also a challenge in the spaces I've been in. I've met self-identified straight Muslims and say I would love to support but at the end of the day God, I can't support you, we can be friends, but up to a certain point until I guess, you're going to hell. The flipside and implication of that is, 'there are some things I just can't learn from you about a Muslim. There is a limit to what I can learn or understand about God from you. You have to learn something from me. You have to learn from the status quo.' But if we only listen to status quo Muslim narratives, straight cisgender Muslim narratives, what does that do to our development of our personality and sense of purpose? What does it do to the stories we tell ourselves? So my third observation is this idea that sexually diverse Muslims at the very least I would say, people who grew up believing in God and then realising that they weren't what was sexually normative, and that affects their relationship with God, even though these two things are very separate. And it shuts them out, they have to learn the hard way, I had to learn the hard way, that social acceptance is important, but self-acceptance is a spiritual experience. I had to learn to blame institutional failures instead of always blaming myself. And I had to learn not to erase myself so others like me won't know that I'm out here. Being on this call is something I am terrified of doing, but I am convinced it is the right thing to do to not erase myself and to not talk about these things I have to say, to value myself enough to realise that even though I don't perform reproduction I'm still a valid Muslim, a valid believer, a diverse Muslim ancestor in the community sense of the word, not the family member sense. Yeah. That's sort of what I was thinking about the digital age, the internet has been very helpful in coming me to understand all these things. I didn't just rely on material that was available to me at a local level in only one language.

aw: So many good points. I don't even know which ones I should take up! first of all, I agree with you that the notion of diversity, which is an aspect of gender identity or sexual identity is just a part of the spectrum of human diversity. For the work that I've been doing since I had an opportunity to do some research, I literally started to make two sets of document files and one was about the various aspects of gender identities in their complexity and beauty, but the other was with regard to children who have different neural processing modalities. We have hundreds of expressions of autism today and a hundred years ago we had zero. And that means either that it is new and it might be, I don't know, or it is only newly understood as an aspect of human diversity.

Liy: Yes.

aw: And the intention is to take the innocence that we feel towards our children, because they recognise aspects of autism even in babies. So to take the innocence and say the harm that comes when their particular operating processors, when their neurodiversity is not acknowledged and nurtured, the harm done to this innocent is exactly the same kind of harm that different types of transphobia, queerphobia, biphobia happens with regards to people whose expression of their gender identities does not fit the heteronormative dominant model. And so to deconstruct as you said, to not have it just about sex because if everybody is performing sex when they have an opportunity to perform it and they're all performing it in accordance to their orientation, and yet when you reduce it to only literally the genitalia what you're saying is there's not a whole being, and the aspect of the whole being for me is so important. And that's why I call my research sexual diversity and human dignity, because there's no reason why our humanity should lose their dignity and part of my learning that is actually the relationship I had with you. So i want to talk a bit about the tawhidic paradigm. because in your work, which they're going to share before we close this reading. In your work you made an explanation of the tawhidic paradigm and you sent it to me to make sure you quote unquote "got it", but the dimensions you shared really have made my heart skip a beat. So please, can you talk to me a bit about your experience with the tawhidic paradigm?

Liy: Wow, okay. The tawhidic paradigm changed my life amina! I'm just going to start with that. I took so long, I think... as you mentioned the tawhidic paradigm is in the book, I think it was the last part of the book to get written, because I was so nervous about summarising what you've been talking about for essentially decades, right, into 2-3 pages of my book and say 'here's a summary of amina wadud's theory on this one topic of conversation.' But how I understood it. I knew it originally came around to create more symmetry in the imbalance between genders, codifying symmetry on the basis of that. And I still think that's important. Before I continue I should say that this whole struggle to decriminalise sexual diversity from an Islamic framework can only happen if we continue trying to democratise and do the same for women. There is just no future we are in, where queer Muslims get liberation and justice first before Muslim women do. On that note, that's how I understood the paradigm first and foremost. This is for gender equality, this is important, I should take note. I was lucky to be in rooms with you when you were explaining women and making note of it, and thinking about how would I tell it as someone who doesn't always see themselves as a woman. There's something there about, I have to pull up the explanation I wrote. I know I said something there that was really sci fi and I don't want to paraphrase it wrongly.

aw: No worries, take your time. We are here for you.

Liy: I was nervous to send this to you because I know that I wasn't writing about it from the perspective of gender equality, I was trying to write about it in a much larger sense that could be applied in the way you're talking about when it comes to gender diversity or biodiversity as a whole. And in it, I mentioned this idea of thinking of tawhid itself as a core operating system that connects my physical and metaphysical realities. So this is a bit of a fun thing, I think you met me through encounters with tech, my perception of tawhid was also from a perception of tech and sci fi in a way. Much like my devices, my phone, my laptop, I need to upgrade my operating software to keep myself functional. What does that look like? Upgrading my tawhid is to think about how my understanding of Allah changes and affects my beliefs as I grow. When you get a new phone there's stuff in there that's pre-installed that you don't always want and use. That's also how we enter the world. As we grow, we look at the things that have been installed and ask is this something that benefits me and helps me understand the world better and how to use this thing better, or is it bloated software that has been in here because of contracts and arranagements made between companies for a long time and it doesn't serve me actually. I think about accepting downloads others have made for me. I think about what if I learn to code my upgrades for myself. Because I'm not seeing what I want to see reflected in what i am learning about faith, especially from the perspective of representation. I would like to read to you the last paragraph of my summary of your tawhidic paradigm: Since Allah is a circle with the center of everywhere and the circumference of nowhere, inside each of us is an essence (dhat) reflecting our union with this cosmic design. And we can choose to ignore this transcendant reality and emphasise the illusion of external superiority over others, or we can recognise the transcendent reality in all human beings and relate to each other in a reciprocal way. I don't know if you've seen the movie Matrix, amina, it's a classic. At the time the creators had not come out as trans women yet. So brought to you by two trans women sisters is this vision of a world where the world is essentially a hologram. I have that in my notes somewhere, that the dunya is a hologram. And we are all non-playable characters. We were given essentially free will, to play this game however we wanted. And I think that is a measure of how much Allah believes in us. Because how much you believe in other people is your capacity to enable an environment in which they may or may not disagree with you right, and I felt like Allah gave us an environment that totally permits complete disbelief in Allah and in a way, I feel that Allah believes in us more than we believe in Allah. So to think about this whole sci-fi reality, the idea of the world being a hologram, plugging in and out and thinking about pre-installed software, it all fit in with the tawhidic paradigm for me. It was really helpful thinking through gender as a whole. While we're on biodiversity, i think silence is quite important. and i think the only kind of biodiversity that Muhammad pbuh could not be silent about was racism. It's 2021 and racism is still the thing. I feel like sexual diversity was a huge issue in terms of saying who we can or cannot sleep with, that would have maybe been worthy of mentioning and since the silence on that was so loud what does that mean, what does it mean that we see a silence of specific rhetoric, in terms of informing our priorities. I hope I'm making sense.

aw: It's interesting. People have asked me just in terms of the normative hegemonic binary of gender, people have asked me, why didn't Allah talk about this or that, or say this or say that, the Prophet upon him being peace, and I had to answer that in a theological way. In terms of diversities of gender identities and/or sexual orientations, I think that we all are going to be dependent upon notions of diversity and the way in which the Qur'an tackles that rather than the specifics that we currently identify with, because otherwise, it's endless. I think the endlessness of human evolution and diversity is supposed to be that way. And therefore not everything is answered. So because for example, the Qur'an does not condemn the institution of slavery, does not mean I do not draw inspiration from the Qur'an from my own location of disagreement with slavery. So I also say that maybe the Qur'an doesn't give me every single detail, but I do see that there is a trajectory. And if we follow that trajectory and make application in the way these things manifest in life, then we are more hopeful. I often take a from a friend's description of the Qur'an as a cookbook. When you're really a cook, you don't follow anybody's book precisely. You augment or you take away, so and so has an allergy to cilantro, so I have to substitute parsley instead. You enhance and take away from the recipe in accordance with what you already know. With regard to the Qur'an, it is not a literal thing which we take, it is a dynamic thing which we interact with and in our act of participation in its meaning, then we are allowed to have a diversity of locations on different ways in which things are articulated. Then it's not a prison, it's a tool of liberation.

Liy: I have a response to that and a question for you. It comes back to my point earlier from how we define ourselves. I totally relate, as I have received from queer Muslims, queer people, I've looked for myself in the Quran and I couldn't find it. How were you looking for yourself when you looked for yourself in this Quran? And it comes to how do we let other people define ourselves? I've always had an issue with say LGBT as a label because I don't like relating myself, describing myself on this relational level of who I want to fall in love or have intimacy with. How can I define myself based entirely on who I want to be with? There's got to be ways of defining myself that hold even when no one is around me. Even when we're completely alone, we're never alone because Allah is there. This idea of, if I am not with anyone right now and I am in a room, what sexual am I, and why does it have a label and why does that have to be the label? If I am looking for someone who has certain sexual relationships in the Quran we're going to talk about Lut and zina all over again. I list many other verses in the Quran, about Allah talking about what They've made. The verses that inspired [The Signs In Ourselves] is the idea that there are signs, ayah of truth inside yourself. It's not just 'I have to look outside, I have to find in the Quran, in a scholar, a hadith, that tells me what Allah loves me. When Allah has said multiple times in the Quran that there are signs inside you, I've made you mates among your own nature, every body has different natures and tastes, why can't we use those verses when we think about how "I couldn't find LGBT-friendly verses in the Quran." We have to stop looking at ourselves from the perspective of the people who want to reduce us to sexually deviant beings and start thinking about us as outside the bedroom, for starters, and in public life. What kind of dignity do we get? We have people who are... this is the funny thing, every Muslim I've met, knows someone who is sexually diverse, they know someone who is trans, gay, lesbian, bisexual, asexual, and yet they still want to hold this idea that their friends have a limit on how much Allah can love them. It's a little weird for me. Who loves your friend more? What kind of world have you rationalised yourself in which you have so much love and compassion for your friend that you can continue being their friend but Allah ultimately does not? What are you saying about yourself as a person when you talk about sexually diverse Muslims? And it's worthy to ask because straight Muslims talk about us a lot.

Liy: I quoted in the book something you said, at an event, to Muslim women around the world and you said in our time, diversity is the challenge to our current realities and you said for me in terms of Islamic theology and ethics, how we deal with sexual diversity and ethics will be the ethical question of our time. Can you explain that a little bit more?

aw: It piggybacks a little bit on your thing about "I don't see lgbtq in the quran" and my new favourite thing that I learned with regard to text is the embrace of ambiguity. That is, how to take the unsaid, and flesh it out for meaning. And I got that from doing the research on sexual diversity and human dignity. I came to too many places where it was simply not answered. And I all of a sudden realised, 'Oh, it's the unanswered, the unspoken, which is itself a tool of guidance.' So I proposed that for most Muslims, there is a generic understanding of the kind of comprehensiveness of justice, and in the gender binary context of social justice work, we said how can there be justice if Muslim women don't experience it? So we challenged justice as experience. The question of Islam being for all times all places and all people. It's universal, not just for Muslims from Malaysia or Saudi Arabia or black or white, it's supposed to be all times and places, it cannot have a comprehensive closed door relationship with people whose sexual diversity is not a part of the heteronormative dominance. That means for your friends who say well I love you cause you're my friend but Allah cannot love you, what they're basically saying as you've noted is that there's a limit on Allah but somehow they are above that. We need to understand that if there is no limit to Allah, then Allah embraces everything in the creation, and that includes people whose sexual location is not a part of the hegemonic binary. And I say it is the question of the future because this cannot just be emotionally 'Liy is my friend, and I want them in my life' it has to be, Liy is a person, I am a person, and my personhood and their personhood is simply a reflection of person in the context of Allah's creation, and there's no other criteria or evaluation that has to come in. Not whether I love them or not even. It has to move beyond... of course it's important to start with the personal, because that's how people come to open up. But it can't stay there, it has to go to the ethical. When it goes to the ethical then it has to be formulating some comprehensive notion about how the universe works, and as you said, that has to be within an operating system that includes everything within it like tawhid. For me, I'm using this as a challenge to people whose comfort zone within their entrenched heteronormative dominant binary hegemony that your comfort in that location is an intentional reflection of the limits that you believe that system is operating under. And I personally don't believe there is a limit so you need to check yourself. That's where it went.

aw: I want to share with you and you can respond how you like. When we were holding a Musawah workshop sponsored with SIS in Cyberjaya and Friday came along, I was approached about holding the jumaah, since I am the lady imam. And I always go back to if you build it they will come. I experienced the most amazing jamaah where every single row was participated in by a member of our collective. Not everybody got to play a role, but instead of having one or two or three people, we had a jamaah group that was formed by a group of orchestrators. I was so smitten by this experience. You were the major motivators of helping to organise that.

Liy: I remember that jumaah, it was a very emotional jumaah for me. That was my second or third time ever meeting you and I was still blown away by being in the same room with all these people. I remember that jumaah particularly because of a very stunning khutba before you by a local poet and I think it was the idea of expansion, she quoted I think it was Musa's doa to Allah to expand his chest. That was an emotional jumaah for me, I remember you said something there about solidarity for LGBT Muslims. I don't know if YOU remember saying this! It was a theme that had come on and off at this event. IT was interesting being in a room with Muslim women feminists at the time who were very clear about working on all the issues they needed to work on but having to make more and more room for the reality of sexually diverse Muslims among them. And anonymously it had come up a day or so before that someone had put on a post-it once they were realising that some people in the room were LGBT, said how can we accept LGBT people? And I remember a friend of mine at the meeting standing up and making a bit of a statement about that. And it gave everybody food for thought. We are literally among you and you're still asking this question, it's something to think about. And I wasn't sure if anyone was directly acknowledging it throughout the event. And you acknowledged it that day. and it moved you to tears, you were saying it wasn't always easy to think about the kind of struggle, the way of standing up for them, but you were compelled to think about it, because when you were being cyberbullied, the ones that always held solidarity for you were the queer Muslims. and that moved you into thinking I need to somehow do the same thing. I remember looking at you tearing and then also tearing up myself, I just wish more straight Muslims thought about this more, this idea of how active these people that they speak about are in their own communities doing work. There are so many examples in The Signs In Ourselves of marginalised and persecuted transwomen in Indonesia, giving haircuts for free during Ramadan. That was what I thought about during the Musawah gathering. This arc that culminated in a moving gesture of solidarity from you to people in the room. That was extremely moving. From them on I remember anybody, because I meet a lot of LGBT people who are skeptical of who supports or defends us, I would say 'amina is one of them, I was there I saw it happen!' Whether you like it or not that is part of your legacy already amina.

Liy: I had this idea in late 2019 after being in all these spaces and thinking about all the things I've mentioned with you today, about what we could learn from queer Muslims. I think I was mainly obsessed with that because if we can even get a collective ummah to admit that they have something to learn from a Muslim even though they're sexually diverse, I think we can open the doors to a lot of other discourse. The intention of the book was to write a workbook. It was actually meant for, written for, and by queer Muslims.

Liy: These were the two Quran verses that inspired me to write this whole book, the first being from Surah Adh-Dhariyat. "On earth there are signs for those with sure faith, and in yourselves too, do you not see?" and the second being from Surah al-Fussilat, which is "We shall show them Our signs in the universe and in themselves until it becomes clear to them that this is their Truth. Is it not enough that your Rabb witnesses everything?" Which is a great question to ask on the worst days. So these two verses told me that Signs of Truth exist in nature and in people, and not just in the Quran and Sunnah. And there are sources of knowledge from here out to the cosmos and deep within the universe of our own bodies. This gave me so much peace to find out because it didn't feel anymore that I had to fight with the truth I knew to be true in my heart, vs. what people were saying around me. So I thought instead of spending energy countering what others say about us, what if we collectively built our spiritual strength and reclaim our access and authority of the Divine? What if that's what queer Muslim collective care looks like? That we don't start the next generation on empty. Because a lot of sexually diverse people who are exploring ways out of spiritual poverty and thinking about embracing different faiths, usually they feel kicked out of being a Muslim, and then they feel like the first queer Muslims to have ever existed in the world, which is just not true. What if our lives are rich with signs from us to learn from? And I wanted to make a project about that. Especially because a lot of us are healing from the trauma inflicted by people using faith as an excuse.

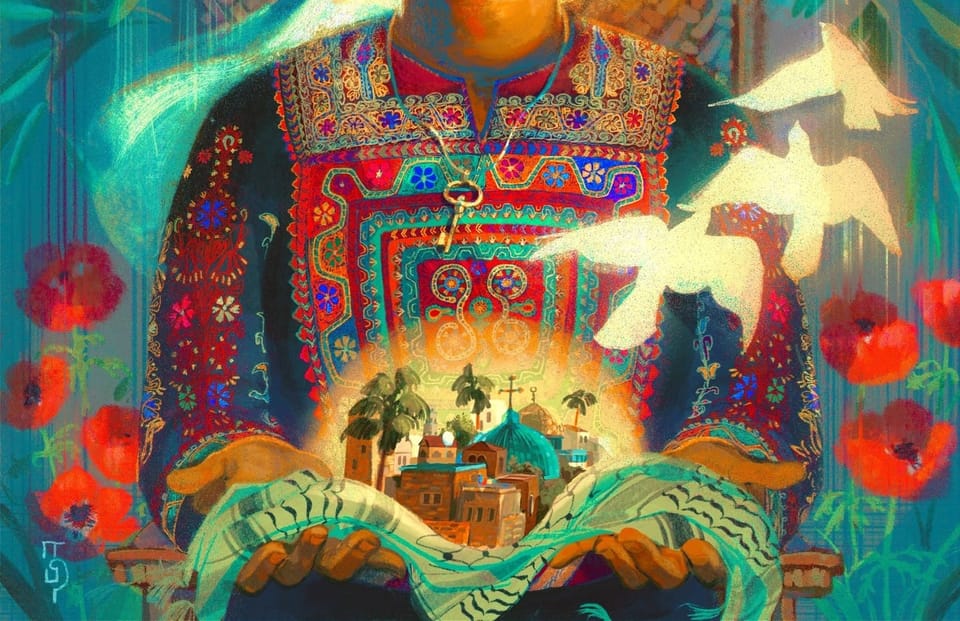

Liy: So there are two names on this book. The first is mine and the other is Dhiyanah Hassan. This book is so visual. What's in here are queer Muslim stories. The heart of the book is based on a dozen interviews with Southeast Asians. My only qualifications is that you have to self-identify as a Muslim, even if others say you are not, and you also not have to be a cisgender heterosexual. It has voices from 14 other countries as well. The book has art, lots of art, it starts off with the most rainbow al-Fatihah ever. It's also a workbook. 13 exercises in there for the self and the collective. Since I know amina, you like to draw and colour a lot at meetings to help you focus, the exercise I attached to your tawhidic paradigm module, was 'you just have to draw your own prayer mat.' People say it's their favourite exercise. And then there's four helpful sidebars. So you're one of them, specifically the tawhidic paradigm. Although I recognise that your work is full of lessons for us, I wanted to take the paradigm as that essential starting point. And then there's also Dr Ghazala Anwar's portal of rahma, and a whole section on challenging the prioritisation of reproduction through work from queer interfaith Indonesian activism. I'm so proud of the people that stepped up to be a part of this book. I asked them these questions and they answered. I recorded their answers and sorted them out throughout the book. That's what you get when you read it, you'll find questions that I think not only people have wondered about queer Muslims, but also queer Muslims wonder about other queer Muslims. What is it like to be queer and Muslim in other countries. So many people were generous with their answers and experiences.

aw: And you get this beautiful amazing work for free! I spoke with Dhiyanah about coming on and talking a bit about what she does with art as therapy. We're trying to work out a date. Every single page is beautiful in both its content and its expression. The idea of centering on queer Muslim spiritual self-expression is nothing short of stellar. It's such an amazing thing to do. There is nothing like this out there. And one of the ways in which my own kinship with the queer Muslim community grew was to be in live session, usually retreats, where the level of spiritual enthusiasm was unparalleled to any place that I had been including going on hajj. When I made this critique at one of the queer Muslim retreats I was in and take the energy of the queer Muslim spaces I've been in where we do dhikr in the morning, and prayer, and jumaah and to take that energy with me to hajj because my hajj had been rather spiritually unmotivating. A queer Muslim organised for me to be the spiritual resource person for a queer Muslim umrah, so I got to get my two things together. This publication allows you to, I don't know what the digital language is, in the old school terms we used to have a book, you put it in your hand. You can have this resource on your device for free!

Liy: Which is in your hand!

aw: And I'm telling you now as a used-to-be retired now returning professor of Islamic studies, this is unique. And not only unique but the beautiful unique, because there's unique and it's weird. This is just such an amazing thing. I think everyone will see themselves reflected here. And the whole point I believe, if I might jump in to say this, the whole point in about the signs in ourselves, in your own self as the Quran says, is to highlight the reality that we are all mirrors that reflect the reality of Allah. And this work really lets you see that. And I am hoping that you get a million downloads. And go down in history as go down in history as the first person to realise that focusing on the spiritual realities of queer Muslims is the way to go forward towards equality and justice inshaallah. I wish you all success. Some comments in the chat: 'every day i continue to be awed by this book, both content and aesthetics. You can see how much thought and care was put into this work. I expect no less from Liy honestly!'' 'This is gorgeous, I can't wait to read it.' 'Our signs, our choices, are how we actualise God's gift in ourselves.' I'm hoping someone will ask a question or make a comment before our next five minutes are up. Because I have so much I can say. I'm in love with Liy. I'm in love with her from the very first time I met her. The fact that she made me feel not stupid with regard to the thing that I am still struggling with, which is the reality of the digital world.

Liy: You're doing great.

aw: I feel like for my age, I am not doing too bad. I hope you don't mind, we hold small group sessions in my Patreon page, a place for us to spiritually attune and relax at the same time, because it's not published. I would love to go through this in some of these small group sessions. Because I really want to see this promoted in other places. The very fact that even for my own self-identity, my evolution and understanding my orientation. By the way I identify as queer because I have been involuntarily celibate for more years of my life than I care to count, and for the majority of the years of my life. And that means my sexual orientation is not always known to me because I have no way to understand what it is.

Liy: Someone needs to date you!

aw: I am open to more than one possibility. I definitely believe I can love a woman as much as a man and a trans as much as a cis. I identify as queer and I also identify as nonbinary. And that is because tawhid has really helped me to understand that we also need to integrate the masculine and feminine of our own bodies and being our own modes of operating as a way to be able to achieve our highest self. So at the moment I am no longer a straight ally. I clearly identify within the queer Muslim context.

Liy: Yay! We have a queer elder!

aw: We have a lot of queer elders! A couple of people in that age range. Al-Farouk [ ] is going to be my next guest. He's a queer spiritually oriented activist who has been at it for more than 20 years. I look forward to that. Second weekend in March. I see that this year in particular I want to highlight the activism, scholarship, spirituality, love and challenges as well as contributions in other ways for queer Muslims because it is my goal that at the end of the contract that I currently have that I will have up and running this study center for queer Islamic studies and theology. So I thought what I should do along the way is highlight these amazing friends, like Liy who I am happy to call a friend. I love that they have grown in their own estimation of the significance of the contributions that they can make towards humanity at large. I think this book, The Signs In Ourselves is something we will always be looking back on and future generations will simply piggyback off this to create more amazing projects. I think the inspiration to move forward with this at this time is really nothing short of a complete barakah and so I am so grateful for you.

Liy: Thank you so much. I agree with you entirely. I think we are all reflections of a mirror that is too big for us to see. If I could close it with anything, it would be: if anyone's listening to this and they don't identify as a queer Muslim and they're wondering what am I supposed to do, besides support yall, I think there's lots of way of looking at it and I wanted to close it with a message to those out there who aren't queer. That Muhammad pbuh had a vision of a world where orphans were adopted and loved by responsible adults. And I think that's always a good place to start. There's layers of benefits to adjusting around that. I included those questions in the book. I asked, what if heterosexual marriage wasn't your only option for a stable life? What if every child born was a child wanted and prepared for? What if orphans were adopted and safe at any age, regardless of being teenagers? What if older generations were guaranteed care without the pressure to raise their own caretakers. So solo elderly adults would no longer be one of our most vulnerable members of society. There are benefits to thinking— how do I start dislodging "LGBT Muslims" from just thinking about them purely from a sexual or sexualised perspective, is to really think about the effects of their rights and their capacities through every stage of life just as you would for any other Muslim. If you look at that in terms of policies and care, you'll find stories. You'll find stories of partners who have been together for 10-15 years but can't visit each other in emergency units in hospital because they're not 'family.' Thinking about what the definition of family is, what a family of kinship is and expanding that now more than ever. If we can do that across race, and if we can do that across generations, I think we can also do it across these ideas of our innate diversities. Thank you, I see someone in chat saying this is a brilliant starting place. I'm glad you think so. Thank you for listening and for having me amina, I am so blessed to have you in my life.