The Tawhidic paradigm for human rights

This is a brief adventure into the world of Islamic ethics. Tawhid is a fundamental Islamic principle, often translated to as 'monotheism', but as we'll see, there are more layers to it than that.

This is a humble (and frankly nerve-wracking!) attempt to briefly summarise decades of dr. amina wadud’s life work into an accessible starting point for queer and sexually diverse people. Please read amina's 2006 book Inside the Gender Jihad and their other work for the tawhidic paradigm in their own words. I felt the need to include this essay in the The Signs In Ourselves workbook because of the paradigm's practical implications; it underlies much of Sisters In Islam and Musawah's work in an earlier essay sidebar.

It's exciting to imagine the potential of this tawhidic paradigm as a framework for generations of queer and diverse Muslims.

The Tawhidic paradigm for human rights

Liy Yusof, after dr. amina wadud

This is a brief adventure into the world of Islamic ethics.

Tawhid is a fundamental Islamic principle, often translated to as 'monotheism', but as we'll see, there are more layers to it than that. The tawhidic paradigm asks us to consider how our recognition of A!!ah's singularness manifests in the way we live life.

Why does this matter?

Knowing you have a personal relationship with God doesn't mean it is then immediately clear how to connect that to a sense of authority or ownership— to believe you can fully participate in producing knowledge from within an Islamic framework and engage with primary sources.

Claiming that authority with conviction goes a long way to resisting mono-narratives constructed from years of blindly accepting long-held interpretations of the faith (including our internalised sexism and phobias of diversity). Through their work, amina wadud offers this paradigm to us as a structure for faith and activism. She describes it as the reason why she became Muslim.

I've come to think of tawhid as a core operating system (OS) that connects my physical and metaphysical realities.

This is a metaphor I adopted after encountering amina wadud's explanations of the tawhidic paradigm a few times. Much like my devices, I need to upgrade my OS to keep myself functional. 'Upgrading' my tawhid is to then consider how my understanding of A!!ah changes and affects my beliefs as I grow — either by accepting ‘downloads’ others have made for me, or learning to code my own ‘upgrades’ for wellbeing and activism. Naturally, this also changes how I see myself along the way.

Theologically, tawhid relates to how A!!ah is not only one and unique, A!!ah is also uniform and unites.

- Because of tawhid, all of Islam exists along the lines of the indisputable and unconditional idea of the Creator's Oneness.

- This is why shirk is the only unforgivable sin (4:116), because it's the direct opposite of tawhid.

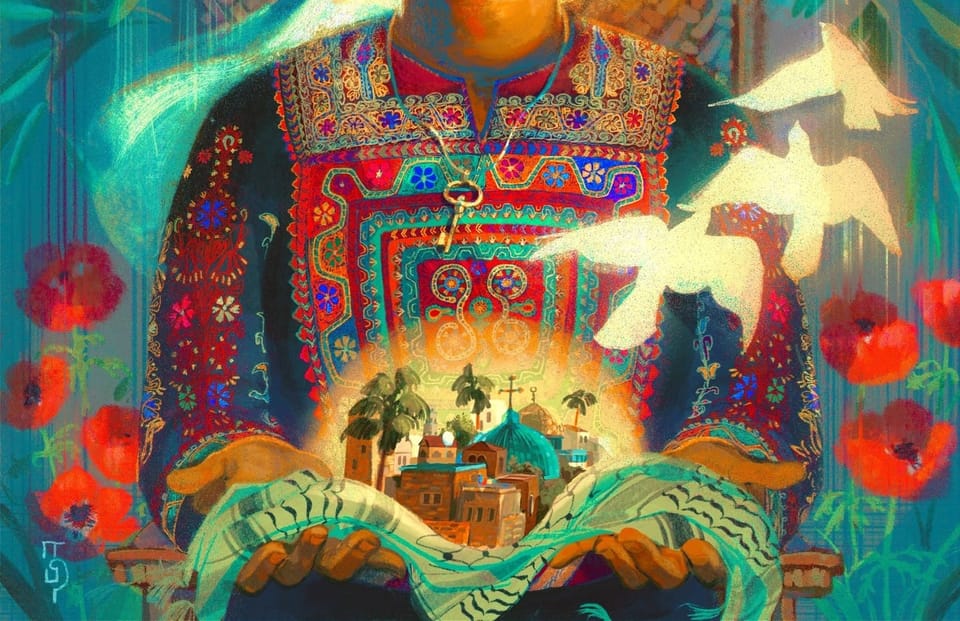

- Because A!!ah is a singularity that cannot be divided yet created everything, everything radiates from one Source and participates in A!!ah's unity.

- This means no matter how it seems externally, ultimate separation between Creator and creature or one and another is internally just an illusion.

When presenting the tawhidic paradigm, amina often shares a quote from the Catholic St. Augustine: “Imagine that God is a circle, the center of which is everywhere, and the circumference of the circle is nowhere.” Applied to a 3D world, amina says God is a sphere of reality:

“A!!ah is present in the most minute thing and also in the most expansive capacity we have to imagine, for example our universe."

Therefore, every human-human relation can be represented as a triad with A!!ah as the third (58:7).

- This can be imperfectly imagined as a triangle, where A!!ah occupies the highest moral point and two persons (or groups of people) are sustained horizontally to each other instead of hierarchically.

- This means, to accept A!!ah's presence is to understand that there can only be a non- hierarchical relationship of horizontal (or equal) reciprocity between anyone else. Divine unity is in itself a social ethic.

This also aligns with how A!!ah only distinguishes between us on the basis of our taqwa (49:13).

Taqwa, often translated as moral consciousness, is also described in the Quran as something beyond our capacity to assess in others— beyond all performance, it is something only the Source can perceive. Yet taqwa factors largely in our own agency in the world (khilafah) — if a consciousness of A!!ah is absent, it becomes possible to think of others along non-horizontal lines of inequality, transgression, oppression, and abuse. "You can't be ethical by yourself," amina says. From an Islamic framework, "the notion of ethical behaviour involves honouring another person because of a deep awareness of the presence of A!!ah at all times."

In the Qur'an, all Things are part of a system of dualism (51:49).

That is to say, everything comes in pairs. Some of these pairs coexist as complementary contingent equals, such as a pair of gloves, or the human and jinn as sibling species. Others are mutually necessary opposites, such as day or night, up or down. All of creation is interconnected this way, but since A!!ah is not like Things (42:11), A!!ah is the tension holding the pairs in balance and harmony while occupying the highest moral point at all times. As amina points out, "The Qur’an never says we were created from a male person. The first person was Adam, an entity that has what is essential to all of us — a nafs and a soul. When Iblis says 'I am better than Adam', he places himself as better than the other (istikbar), and that is the foundation of all forms of oppression and discrimination.”

The tawhidic paradigm also reflects itself in other sources of knowledge.

Some examples are the golden rule of reciprocity, the Mandelbrot set (sometimes called the thumbprint of God), or the yin yang, an ancient Chinese philosophy of dualism. amina references them all when teaching the paradigm, noting:

"There is no absolute positively completely 100% male and only male, there is no absolutely positively 100% female. There is a spectrum. And not only that, looking at that yin yang symbol which is about the masculine and feminine, there is always the manifestation of the other within each."

In presentations, amina also loves sharing this poem she heard recited from a trans person in Africa: "My God is not a woman, my God is not a man, my God is both and neither, my God is who I am."

Muhammad ﷺ was reported to have said "One of you does not believe until they love for the other what is loved for the self."

This is one of the most famous and reputable stories about the Messenger. The hadith reminds us that we can get everything "right" about being Muslim but still fail if we selfishly fail others. This includes the failure to accept diverse people in their full dignity.

In traditional cultures for a long time including Southeast Asia, gender was seen as a spectrum. It was just accepted that some people clearly manifest masculine and feminine in one body," amina says. In her research of the first 500 years of Islamic fiqh, she observes that the fiqh was strongly in favour of inclusion. For example, "the emphasis on creating a prayer space for intersex persons was in everybody's fiqh."

The paradigm inspires us to remove stratification from all levels of interaction: public, private, ritual, political.

In his book, Muhammad: Forty Introductions, Michael Muhammad Knight titled his last chapter Thank A!!ah for amina wadud. He also connects the tawhidic paradigm back to the hadith from earlier:

" This reading of the hadith reflects wadud's Tawhidic Paradigm, in which humanity's role as God's representative on earth means that we must pursue a nonhierarchical human unity that mirrors the perfect unity of A!!ah. When we violate our shared humanity with ideologies of patriarchy, homophobia, transphobia, racial and ethnic supremacy, patriotism, religious bigotry, or ableism, we perform a kind of idolatry. [...] Recognising A!!ah's tawhid means recognising shared humanity, which in turn means affirming others as equally deserving of human dignity. wadud's prioritisation of this hadith hasn't led her to any "loosey-goosey" spirituality or withdrawal from ongoing struggles for justice. She has fought and suffered for her theology and its real-life ethical consequences."

Since the ultimate intention of Islam is reciprocity and not hegemony, this ethic was first applied to gender relations in the family by Sisters In Islam and Musawah, and can be applied to all human relations. amina wadud lists its potential applications in human rights debates "including women’s rights, LGBTQ rights, antiracism, antisexism, anti-ableism, and other counter-oppression movements within an Islamic framework."

Since A!!ah is a circle with the center of everywhere and a circumference of nowhere, in each of us is an essence (dhat) reflecting our union with this cosmic design.

We could choose to ignore this transcendent reality and invest in the illusion of external superiority over others— or we could recognise the transcendent reality in all living beings and relate to each other in a reciprocal way.

Since publication, amina wadud is now involved in QIST. See also amina's video Why I am (still) Muslim (10:17) here.

Exercise no.7

from the workbook The Signs In Ourselves

Do it yourself or with others:

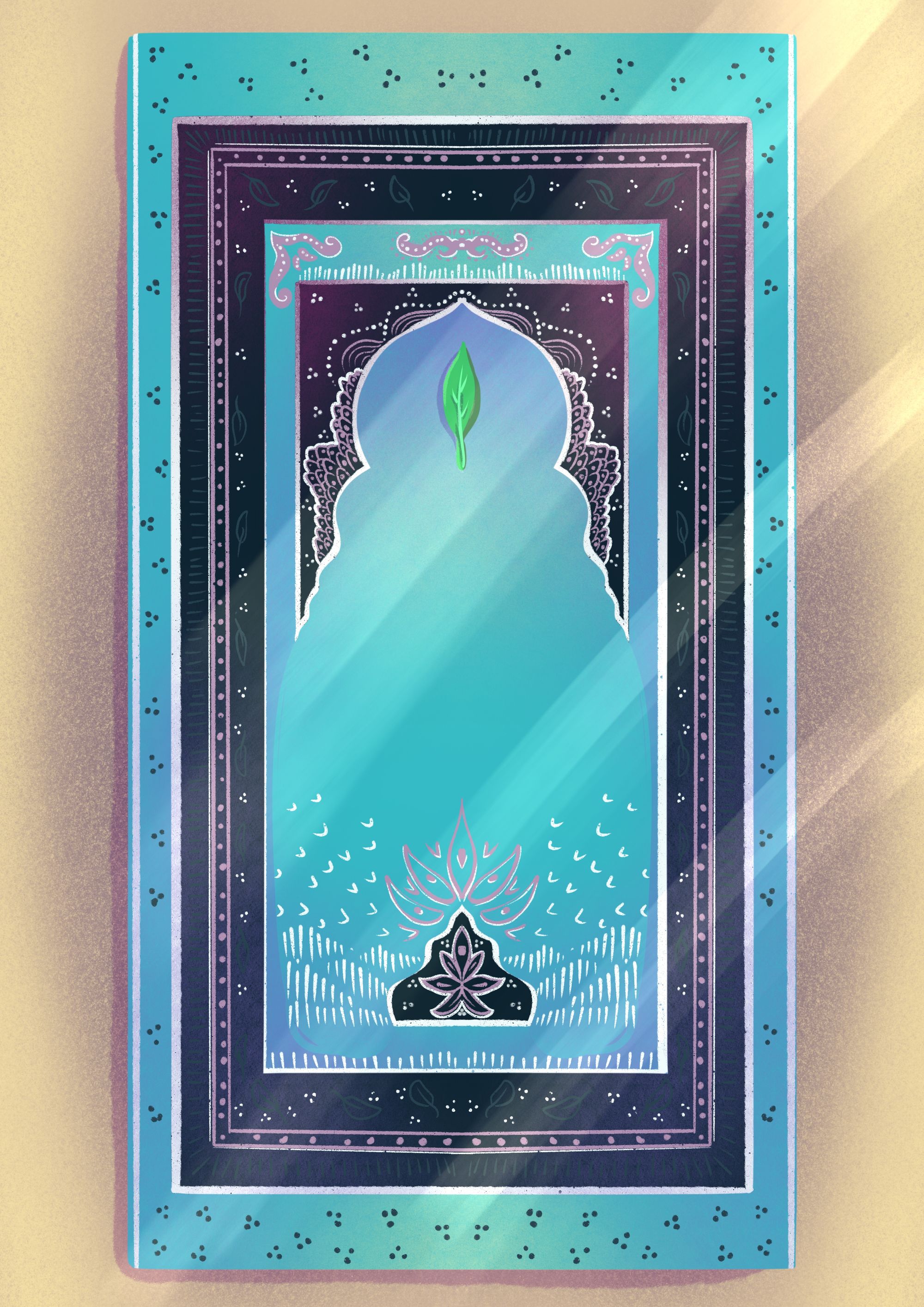

Visualise your own sense of authority and connection to the Divine. In a blank rectangle, design your own prayer mat. Imagine a mat that welcomes your feet, hands, and forehead — a portal that helps you show up. Be as simple or detailed as you like!

This post is adapted from The Signs In Ourselves (pp. 62-65), a queer spiritual wellbeing workbook inspired by Qur'an verses 41:53, 51:20-21, and interviews with Southeast Asian Muslims. Written by Liy Yusof and illustrated by Dhiyanah Hassan, it was made available online in 2020 by the Coalition for Sexual & Bodily Rights in Muslim Societies. May A!!ah azza wa jal accept this offering and bring it to those who need it. Letters and inquiries: qmcourage [at] gmail [dot] com.