Women as authorities and producers of Islamic knowledge

The struggle to decriminalise sexual diversity from within an Islamic framework holds hands with the intergenerational struggle to democratise authority and justice for women.

Have you ever felt sandwiched between choosing Islam without full and equal rights, or feminism but without Islam, and thought to yourself: There must be more than this?

The prominent scholar amina wadud found herself in a similar situation in the year 1995. The author of the first Qur’anic exegesis by a woman scholar critically reading for gender equality was in Beijing witnessing governments of the world adopt the UN Beijing Declaration for gender equality. There, a caucus of gender activists were polarised into two camps that ironically held the same core belief— that one cannot have both Islam and human rights. Both sides relied on uncritical definitions of Islam that presume male privilege. “In 1995, I was still part of the confusion," amina wadud said at a conference years later:

"I was not a feminist at the time. If I had to be locked into a discourse between feminism and Islam, I would choose Islam! But the secularists were confounded by the possibility of equality through Islam, because of hegemonic Islamist articulations of Islam. I didn't want to accept that definition of Islam either. The real eye-opener for me was: Who is defining Islam, and how are they defining it? What are the sources for those definitions? This is when the possibility for Islamic feminism can take place— because when you take agency with regard to the definitions of feminism and the definitions of Islam, you are no longer dependent on somebody else's definition."

Southeast Asia was where she saw a middle path on human rights and formal Islamic knowledge develop.

“I came to Malaysia 30 years ago and worked with the women who would become Sisters in Islam and Musawah because I did not find in my own circumstances— in the US or the MENA region— this cooperative collaboration between formal Islamic knowledge and human rights work to the extent demonstrated here in this region."

Sisters in Islam (SIS) is a Malaysian organisation born from regular study sessions in the late 1980s between a group of professional women in one of their living rooms. They wondered: If God is just, if Islam is just, then why do laws and policies made in the name of Islam cause injustice? They went from writing letters to the newspaper, to working on family law reform, to taking public positions on freedom of religion and expression by the end of the 1990s. In the early 2000s, they were organising meetings with scholars and women's rights groups globally.

They launched Musawah, a movement for equality and justice in the Muslim family in 2009, involving collaborative work between women in several countries that has been going strong despite multi-state persecution of women activists. One of their approaches is to politically challenge the codified asymmetry based on specific Qur’anic passages by proposing to codify symmetry on the basis of other reciprocal passages. "It has the comprehensive capacity to rebuild through text to another location in actual communities," says amina wadud.

"We wanted to try to remove it from the idea that every time we talk about feminism or gender equality, that somehow you must have got it outside of Islam, and in Islam we have our own understanding. That’s usually kind of a doublespeak in order to prevent critical examination of the extent of which gender inequality is a construct, and therefore we have the possibility to construct gender equality."

One of the methodologies used by Sisters In Islam, Musawah, and others in this region in developing their collective knowledge is to consider the reality of gendered experiences as part of tafsir.

amina wadud says,

“If Islam is just— and Islamic intellectual history says Islam is just— and the Muslim woman does not experience that justice, then there’s a disconnect in policy, a disconnect between an expression of equality and the continual participation in inequality. We must prioritise the lived realities of the woman’s experience, because it has to matter when we talk about the perfection or beauty of Islam. Coming to this context and being challenged by how lived realities impact on the phenomena of interpretation and implementation was one of the most beautiful things that happened to me.”

A clear example of incorporating women's lived realities was in the first Indonesian women ulama congress (KUPI) in 2017.

The congress arose from a need for a different fatwa forum where women were the full subject of fatwa. After much discussion, KUPI's inaugural congress made the following declaration:

- Sexual violence is haram both inside and outside of marriage.

- Protecting nature from any damage including environmental destruction in the name of development is wajib.

- Preventing children from any dangerous marriage is wajib, including child marriage.

The forum explored a new paradigm of understanding Islam and fatwa production: They took into account women's biological experiences, their stories of injustice, the state constitution, and scientific knowledge. Some of the women ulama of KUPI not only understood the texts very well, but experienced child marriage themselves. KUPI demonstrated that bringing women's experiences into fatwa production can result in more thoroughly-considered outcomes.

Their declaration had considerable impact: It was a factor for the change of the Indonesian minimum age of marriage from 16 to 19; the Ministry of Religious Affairs approved a proposal for a mechanism of producing more women ulama; the KUPI network was involved in national modules on marriage courses and consulted by the government on issues of female genital mutilation and drafting laws to eliminate sexual violence. As KUPI's success story was presented to a global conference of Muslim women activsts, amina wadud reminded them:

"The task of respect and cooperation between formal Islamic knowledge and human rights work was not easy. We had many roadblocks along the way. But in the end, strategically, it became the most efficient and effective ways of addressing certain problems. In my travels since those 30 years, I have yet to experience this outside of Southeast Asia. Maybe people might want a KUPI of their own in the MENA region, but the work has to be done on the ground. The work to produce it is work that doesn’t just start with the mandate of gender equality. It has to start with the idea of raising human dignity. I think Indonesia and Malaysia are in a unique position in the way to be able to share that, particularly with Indonesia’s pesantren system which already includes women’s leadership in place. There is no separation between knowledge and activism, and knowledge and human rights. And yet, you have to kind of hammer out the rough spots in both to get a dynamic collaboration. Unfortunately, a lot of liberal articulations of Islam disregard the significance of Islamic knowledge history. If we say we want it, we have to examine the ways we are making it happen or preventing it from coming about.”

I'll close this section with a quote in my notes from amina wadud, who is currently invested in normalising the dignity of diverse Muslims:

“In our time, diversity is the challenge to our current realities. For me— in terms of Islamic theology and ethics— the question of how we deal with sexual diversity in the Muslim community will be the ethical question of our time.”

To explore her Islamic framework for resisting all forms of oppression, see The tawhidic paradigm for human rights.

Since publication, amina wadud has been involved in QIST.

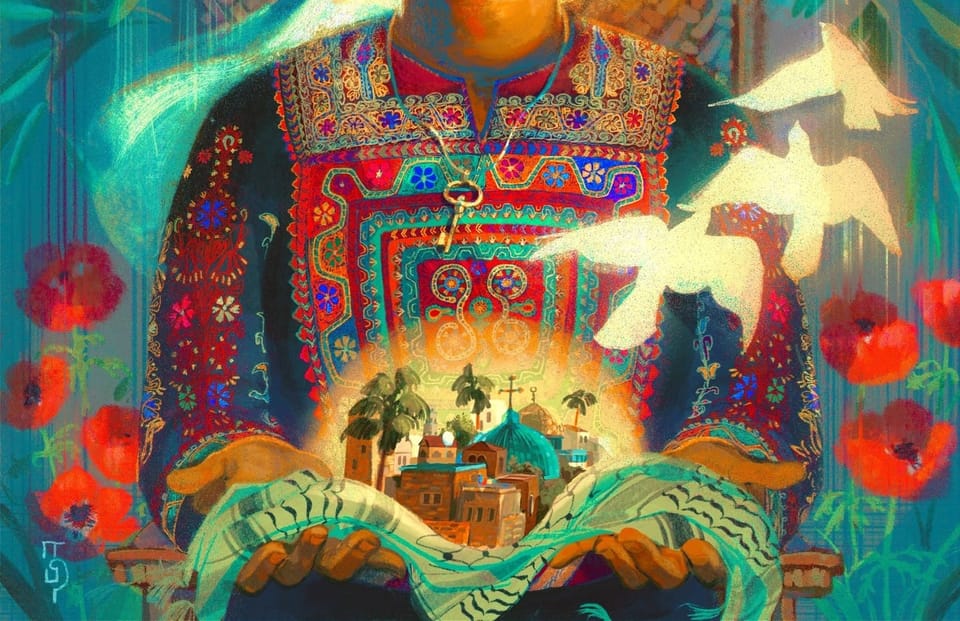

This post is adapted from The Signs In Ourselves (pp. 22-24), a queer spiritual wellbeing workbook inspired by Qur'an verses 41:53, 51:20-21, and interviews with Southeast Asian Muslims. Written by Liy Yusof and illustrated by Dhiyanah Hassan, it was made available online in 2020 by the Coalition for Sexual & Bodily Rights in Muslim Societies. May Allahﷻ accept this offering and bring it to those who need it. Letters and inquiries: qmcourage [at] gmail [dot] com.

The Signs In Ourselves

This post is part of a series of stories exploring queer Muslim courage.

Read all postsSee also:

- Expanding the Muslim knowledge tradition for gender justice

- Listening to interfaith feminists in Southeast Asia

- The official site of KUPI congress