Abusers always use the same moves (and physical violence is not one of them)

What should surprise us about abuse isn't how long it takes to leave, but that one has the strength to endure captivity disguised as courtship.

Intimate abuse always follows the same script. Anyone who has worked with survivors and perpetrators of domestic abuse for many years will tell you this. The patterns of abuse are consistent regardless of where they are or come from; it is a global social phenomenon, a predominantly male one. And these men end up moving the same way, using the same techniques. Jess Hill writes: "Most abusive men, however, would be hard-pressed to articulate such 'tactics'; they reinvent the techniques of coercive control accidentally and spontaneously. This is perhaps one of the most confounding aspects of domestic abuse: whether an abuser is a cunning sociopath or a ‘normal’ man afflicted by morbid jealousy, he will almost always end up using the same basic methods to dominate his partner."

Here are a few tools to help recognise and name cycles of control, terror, and abuse. My intention in sharing these is to possibly help someone I care about or someone you care about find language for their experiences that can open up more possibilities for liberation.

Click to skip to what sounds most interesting or relevant:

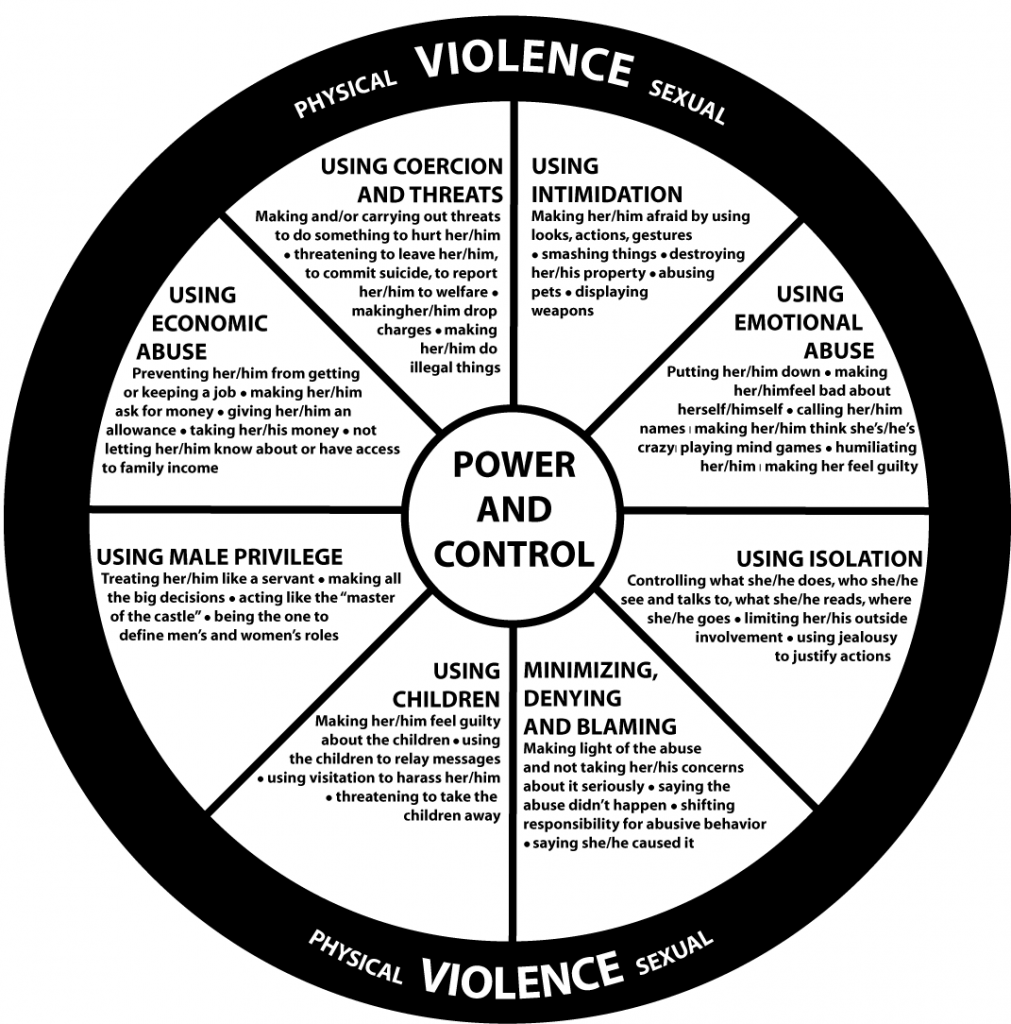

- The Duluth Model Power-Control Wheel is a community-made model to hold abusers accountable, developed in early 1980s Minnesota.

- Biderman's Chart of Coercion to help understand the techniques of coercive control. People who recognise some but not all of these techniques may either be with an abuser who isn't seeking total domination, or are living through the early stages of coercive control, regardless of how long the relationship already is.

- My reading notes after Jess Hill's 2019 book See What You Made Me Do: Power, Control and Domestic Abuse, which focuses on understanding coercive control and insecure reactor forms of abuse. Jess Hill writes from an Australian context, where domestic abuse increased by 83% from 2009-2014 in Victoria. Islamophobia and racism distracted Australians from the fact that their police were being called to an intimate abuse incident every two minutes ("The media, obsessed with Islamic terrorism, had let a gigantic crime wave go virtually unreported").

- Karpman's Drama Triangle for a model of destructive power dynamics in conflicted relationships. Meaning, how people can act in patterns of conflict to disempower others.

- DARVO was identified in the 1990s by psychologist Jennifer Freyd as a common way abusers deflect responsibility and shift blame to their target: Deny, Attack, Reverse the Victim and Offender roles. By reversing the roles, the abuser appears to be the one who is in the wrong. Their targets questions reality, feels guilty, and may even apologise for the abuse they received.

- I close with the perspective that the reason the blueprint is the same regardless of culture or origin is because intimate abuse does not happen in a social vacuum. The template scales at all sizes and transcends gender or identity politics. Consider that settler colonialism is coercive control, and people of all genders and identities can be observed participating in the maintenance of settler colonial projects for proximity to power. This section refers to Lee Shevek, who argues that an understanding of intimate abuse can sharpen one's political analysis of authoritarianism in other forms.

There are more links, quotes, videos, comics, reading recommendations in this references channel I compiled about the architecture of abuse, coercive control, and the power systems that enable it. You can even watch the original 1940 movie Gaslight in there!

THE POWER-CONTROL WHEEL

The Duluth Model, developed in the early 1980s from the small town of Duluth, Minnesota, is a community-based approach to addressing domestic violence. It emphasizes holding abusers accountable while prioritizing the safety of victims. The model identifies abusive behaviour patterns and works to help abusers recognise their actions and for survivors to understand the dynamics of abuse. It is widely used in prevention efforts and offender rehabilitation programs as a framework for communities to collaboratively end domestic abuse.

Understanding that perpetrators can behave differently helps us see the various ways abuse can happen in relationships. From being subtly controlling to outright strategic manipulation, abusers use different yet similar tactics to make their partners feel scared and powerless. Knowing these patterns is important to spot abuse, support survivors, and hold abusers responsible for their actions.

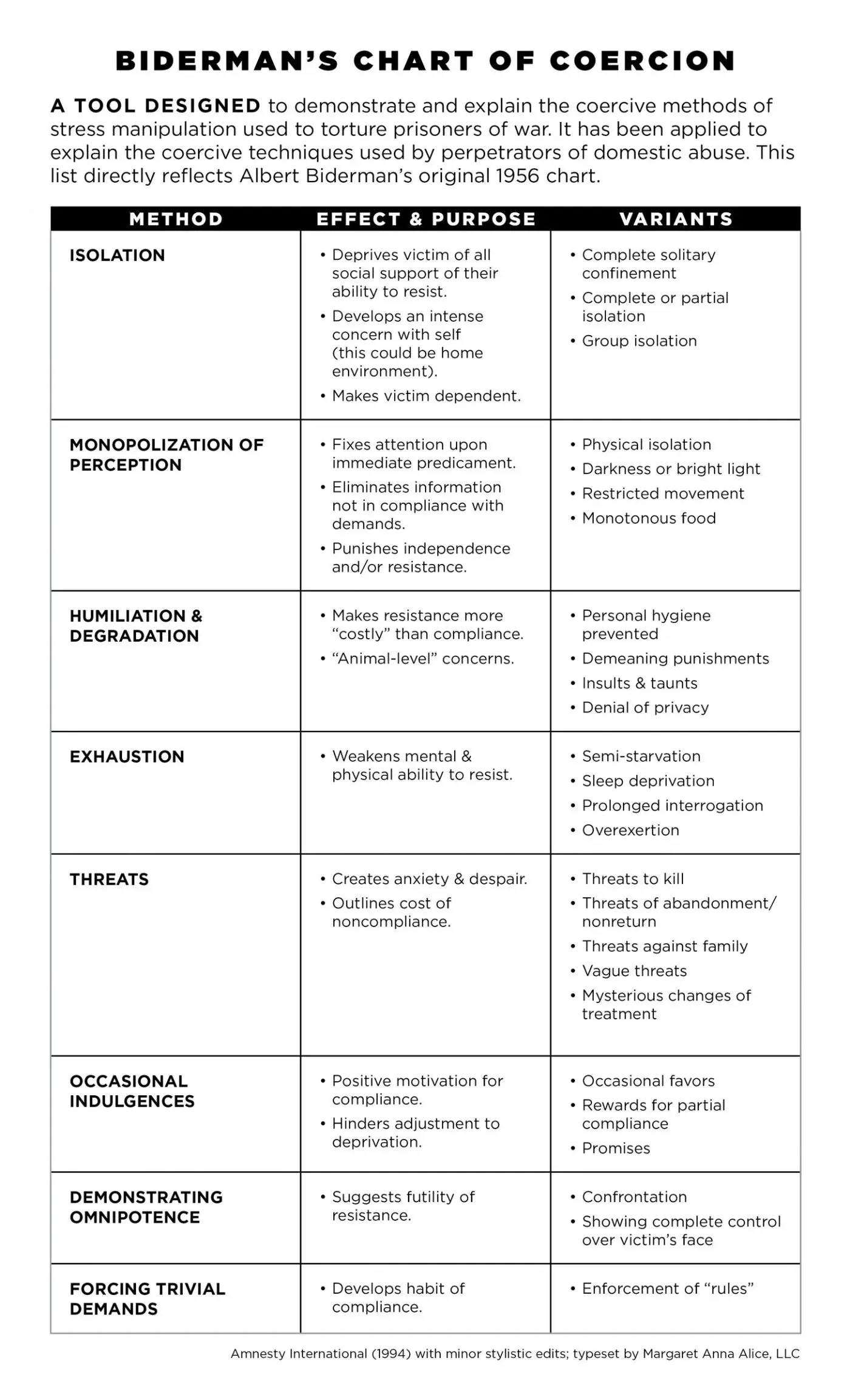

CHART OF COERCION

The Chart of Coercion is a tool created to outline coercive control behaviours. Biderman designed this tool in 1956 to demonstrate and explain the coercive methods of stress manipulation of American war captives. According to Biderman, three primary elements at the heart of coercive control are dependency, debility, dread. To achieve this, the captors he studied used eight techniques. People then realised that the coercive techniques also map neatly to perpetrators of domestic abuse. In 1974, Amnesty International declared the 8 techniques outlined as universal tools of torture and coercion. It is still used to explain the coercive control techniques used by abusers.

- Isolation is a coercive tool to decrease social support and increase dependence on one's abuser.

- To monopolise one's perception is a coercive tool to manipulate reality and control the narrative.

- Induced debility or exhaustion— tiring someone out and depriving them of food or rest is a coercive tool to wear down resilience and increase susceptibility to control.

- Cultivation of anxiety and despair— making threats is a coercive tool to create compliance by destroying one's confidence with fear, anxiety, doom.

- Switching between punishment and reward— alternating between punishment and reward is a coercive tool to manipulate through cycles of positive reinforcement and negative consequences.

- Showing off omnipotence— demonstrations of absolute power or control to assert authority and instil fear is a coercive tool for compliance.

- Degradation is a coercive tool of attacking another's self-esteem to make resistance more costly than compliance.

- Enforcing trivial demands— imposing arbitrary and meaningless rules and tasks is a coercive tool to dominate by developing habits of compliance.

READING NOTES

Here are some of the reading notes I added to my notes system after reading Jess Hill's 2019 book See What You Made Me Do: Power, Control and Domestic Abuse.

- All abusers use the same blueprint of basic techniques to establish power and build bonds of coercive control. Jess Hill refers to them as the blueprint for establishing power: "With each new technique that is deployed, the bonds of coercive control are fortified, and become tighter over time." These techniques have a cumulative effect, so that the longer one stays, the harder and more dangerous it is to leave.

- Coercive control is a strategic abuse campaign held together by fear and specific techniques. It's not just about humiliation, punishment, power grabbing or gaining an edge in a fight. Coercive controllers use specific techniques of isolation, gaslighting, and surveillance to strip their victim's liberty and sense of self. Making the victim fear their abuser is a compulsory element. The aim of coercive control is total domination, not single-issue compliance.

- Physical violence is not a necessary or effective method to gain compliance, but fear is essential. Domestic perpetrators do not need physical violence to maintain their power. It's effective enough to just make their victims believe they are capable of it and fear that violence. Creating an atmosphere of threat is enough to convince the target that the perpetrator is powerful, resistance is futile, and that survival depends on compliance. Biderman's chart had no category for physical abuse, even though it was frequently used. In his research, the most skilled and experienced war interrogators avoided actual violence. It was enough to just create a fear of violence through vague threats.

- Trust is an essential component of coercive control. In North Korean camps of the Cold War era, false friendship was an effective technique that caught American soldiers totally off-guard. In the case of domestic abuse, the abusive process can only begin once trust is established to let their guard down. Once their guard is down and trust is established, the abusive process can begin.

- The first stage of domestic abuse is the development of love, trust, and intimacy. Jess Hill writes that "The first stage of domestic abuse is the development of love, trust, and intimacy." Whether real or fabricated, love yields a sense of security, a call to let down your guard and establish trust. This is when the abusive process can begin; because love is what binds someone to their abuser, and what makes them forgive and make excuses for the abuse.

- Abusers entrap their target by appealing to their most cherished values and capacity to sustain relationships. Since most women derive pride and self-esteem from their capacity to sustain relationships, an abuser is often able to entrap a woman by appealing to her most cherished values. It is not surprising, therefore, that abused women are often convinced to return after trying to flee from their abusers. If one is to resist becoming captive to their lover's abuse, they would have to do the very opposite of what we do when we're in love, which is incredibly difficult. They would have to avoid developing empathy for their abuser, suppress affection they already feel, in spite of their abuser's persuasive arguments and promises that one more sacrifice or proof of love will end the cycle and save their relationship.

- Perpetrators of coercive control make each home a patriarchy in miniature. Evan Stark says what that miniature looks like is that it comes with "its own web of rules, codes, rituals of deference, modes of enforcement, sanctions and forbidden places." The person controlled is commonly isolated from friends, family, other support, and deprived of money, food, access to communication and transportation, and other resources to survive.

- The effect of coercive control is that the abuser becomes the most powerful person in the victim's life. In situations of domestic abuse, the effect of coercive control is the same: The perpetrator becomes the most powerful person in the victim's life. The victim's psychology is "shaped by the perpetrator's actions and beliefs,” writes Jess Hill.

- Addressing control is far more difficult than stopping physical violence. Sociologist Evan Stark said addressing control is far more difficult than stopping men from being violent. Saying "real men don't hit women" is insufficient; it still sidesteps the root of domestic abuse. Men don't abuse women because society tells them it's okay. Men abuse women because society tells them they are entitled to be in control.

- The methods common to intimate abuse match those used by all traders of human captivity. Victims of domestic abuse are not uniquely weak, helpless, or masochistic. In terms of facing coercive control, their responses are no different from military-trained soldiers. Today we know that that the techniques common to domestic abuse match those used by almost anyone who trades in captivity: kidnappers, hostage-takers, pimps, cult leaders.

- What should surprise us about domestic abuse is not how long it takes to to leave, but that one has the mental fortitude to survive captivity by courtship. Resisting coercive control is harder for domestic abuse victims than for other captives because they are taken prisoner gradually by courtship. Hostages know little about their captor. The captor of the domestic abuse victim is not a simple thug or sadist. Before she is trapped by fear and control, she is first bound to her abuser by love. Fairytales and Hollywood movies encourage her to read warning signs of abuse as signs of passion not danger: obsession, jealousy and possessive behaviour. By the time the passion morphs into abusive behaviour, the victim cares deeply and will minimise the abuse to protect him and their love. Love is what makes her forgive him.

- Not all perpetrators enforce tight control regimes. Insecure reactors are driven by shame and frustration to use emotional or physical violence to gain power in the relationship. Jess Hill: "At the lower end of the power and control spectrum are men who don’t completely subordinate their partners, but use emotional or physical violence to gain power in the relationship. They may do this to gain the advantage in an argument, to get the treatment and privileges to which they believe they’re entitled, or to exorcise their shame and frustration." Although Evan Stark refers to this as 'simple domestic violence', men who are insecure reactors can still end up killing their partners too. However, Susan Geraghty who works with a men’s support group says insecure reactors are most likely to confront their own behaviour: "to a large degree, these are men who have lived with violence, have incredible issues around intimacy and have never learned to communicate." Their frustration about this is profound. Women also perpetrate this form of domestic abuse.

- Perpetrators exist on a spectrum of power, from coercive control to insecure reactivity— but the line between coercive controller and insecure reactor is hazy and easily crossed. The spectrum of perpetrators goes from those who don't realise they're being abusive to those who intentionally terrorise their partners. A range of tactics is used on this spectrum, from subtle manipulation to clear threats, all with the same goal of which is to control another person. The line between coercive controller and insecure reactor is hazy and easily crossed. Perpetrators do not fit neatly into a particular category. Insecure reactors may turn into coercive controllers and coercive controllers may pretend to be insecure reactors. Jess Hill: "Some perpetrators won’t fit into either category, especially those whose violence is driven by psychosis. Despite this uncertainty, it’s still vital to understand that not all domestic abuse is the same."

- The home is the most dangerous place for a woman in any country around the world. A UN study reported that of the 87,000 women killed globally in 2017, over half of them were killed by either an intimate partner (30,000 women) or a family member (20,000 women).

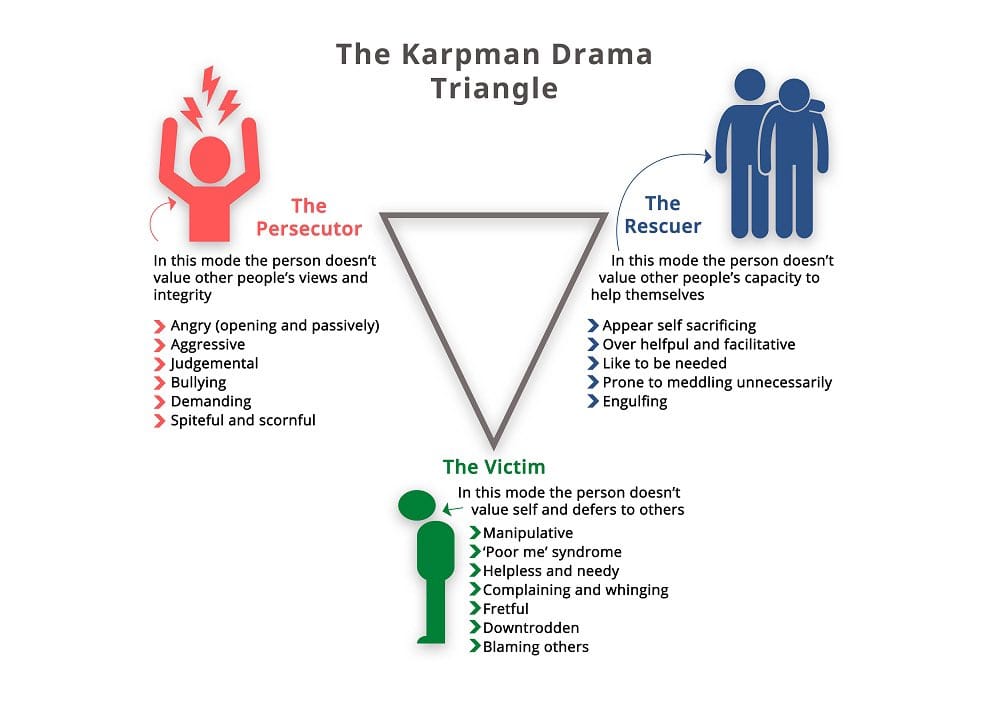

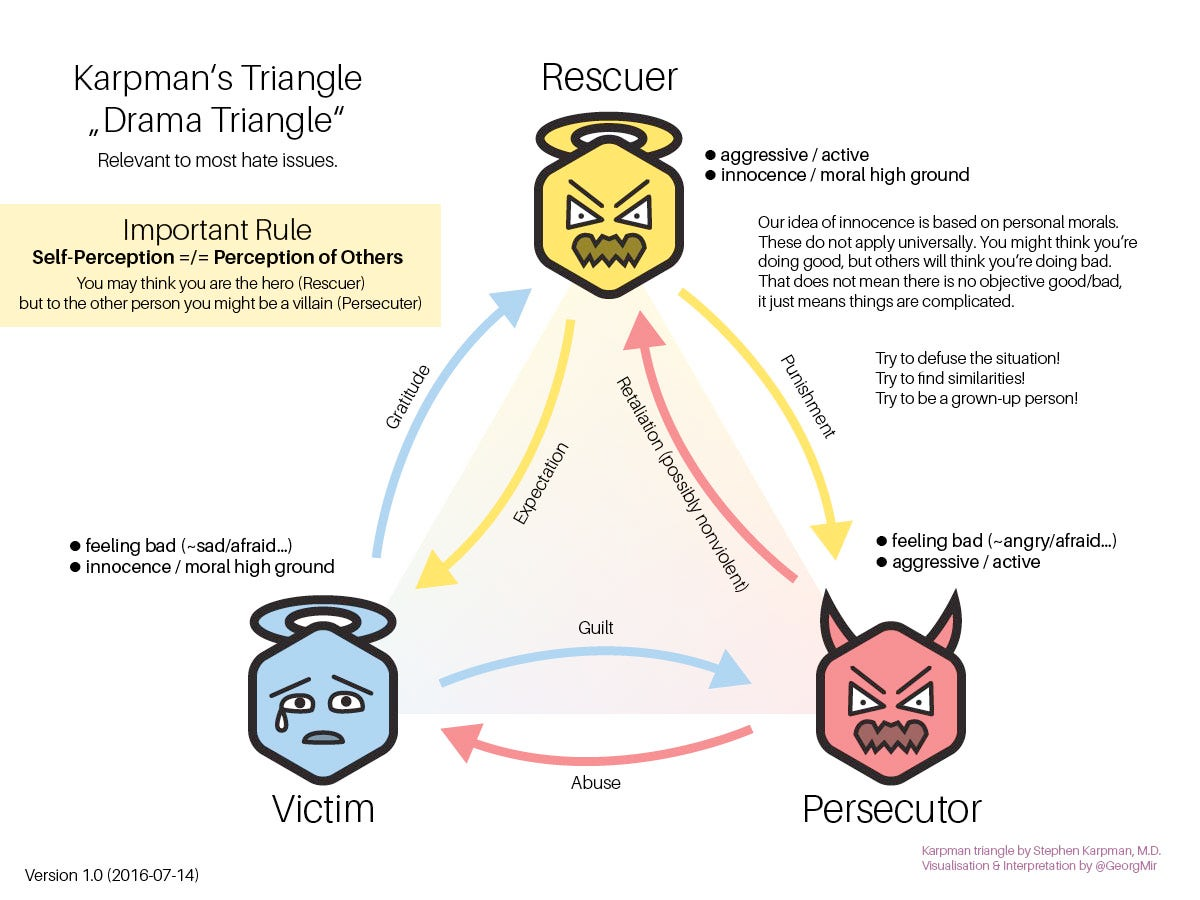

THE DRAMA TRIANGLE

One can take power or coercive control by playing either a persecutor, rescuer, or victim role in a drama triangle to draw others in. Karpman's drama triangle points to 3 ways that people act in patterns of conflict to disempower others— either through outward aggression (perpetrator), providing tokenistic support to save others (rescuer), and to manipulate others by deflecting accountability and casting oneself as perpetually disadvantaged (victim). Though their modality is different, their outcome is the same: gaining power or control over others.

The drama triangle is a model of destructive power dynamics in conflicted relationships proposed by Stephen Karpman in 1968. The psychiatrist developed it to understand power dynamics in conflicted relationships. It is a tool in psychotherapy, specifically transactional analysis. The triangle of actors in this drama are persecutors, victims and rescuers. These roles interplay dynamically in the drama triangle, with individuals often transitioning between them unconsciously, leading to repetitive patterns of conflict and disempowerment.

- The persecutor role in the drama triangle involves blaming, criticising, or controlling others, often to gain a sense of power or superiority.

- The rescuer role in the drama triangle will put others' needs over their own often to feel good about themselves, to feel a sense of self-worth or validation through helping or saving others.

- The victim role in the drama triangle typically feels oppressed, powerless, or helpless, and often seeks validation or support from others without taking responsibility for change.

To escape the drama triangle, first find out which role you usually enter it through. Breaking free from these patterns requires awareness, honesty, and responsibility. It means recognising one's role in the triangle, understanding how they got there, and actively choosing healthier communication and relationship dynamics.

DARVO

5hahem in January 2025 put out an excellent short video series looking at DARVO in context of power dynamics on instagram:

- Welcome to day one of DROP class (diversity, racism, oppression and privilege)

- What is DARVO?

- How to respond to DARVO

- Intro to Power Dynamics

- Power dynamics, standpoint epistemology, and DEI

5hahem has a bachelors in women’s studies, bachelors in political science, masters in social work, and is a practicing licensed therapist and social worker.

IF WE ZOOM OUT

(after reading Lee Shevek)

Why is the blueprint so similar around the world? Why is addressing control far more difficult than ending violence? Many of these resources, research, and frameworks came about from studying the abuse women face from men. Although gender does influence how abuse can be done or experienced, abuse itself follows a broader systemic pattern.

To understand intimate abuse in a less gendered or individual way, it can be helpful to think of how it scales. Coercive control as a framework can be expanded to understand the tactics and values of all forms of authoritarian control; that is to say, authoritarianism is domestic abuse on a global scale. A person who does intimate abuse enforces control on an interpersonal scale to dominate a relationship. They use social, and systemic tools to gain that coercive control. Their actions are a mirror of what norms dominate about relationships and authority in their world.

Lee Shevek (emphasis is mine):

We are taught that jealousy and possessive behavior is an important expression of our love. We are taught that when the people close to us do not fill their role as wish-fulfillers well enough that we are justified in responding to their perceived failure with punishment and manipulation until they submit to our demands to our satisfaction. We are taught to turn interpersonal connections into private property relations, and there is a host of ready-made justifications at our disposal to excuse any number of abusive acts so long as they are done in service of keeping our “property” under our control, whether they are a romantic partner, a child, an elderly parent, or even a close friend. By virtue of our closeness to someone, the kind of relationship we have with them, many of us are taught and come to believe that we are granted some kind of authority over them, and common social practices within our communities as well as state institutions like that of marriage and the family affirm that authority.

Intimate abuse is not just a personal issue or a mistake—it is an interpersonal form of authoritarian power, reflecting larger systems of control like capitalism, racism, and ableism. It runs on the same the broader logic of authoritarianism: the belief that it’s acceptable to dominate and harm certain people to maintain power over them. This logic is reinforced by social norms and institutions like family, marriage, and the State, which legitimise authority over others. Instead of seeing this kind of harm as individual and episodic, realise that it is connected to other social factors that affect an ability to subordinate their targets (see: The coercive control of israeli settler colonialism, 28 May 2024).

Unfortunately, communities and organisers often treat intimate abuse as individual private problems, fearing that addressing it will weaken the movement. This allows abusers to remain protected while survivors are silenced and excluded. The groups suffering abuse are those already marginalised by society, and the most successful abusers are those with access to tools of systemic power. By adopting a systems approach, we can see abuse not as the result of individual or gendered pathology but as a reflections of broader social programming re: power and control. This can broaden our understanding of abuse beyond gender or identity politics and encourages us to challenge the structures that enable abuse to happen at all (see: Intimate authoritarianism: The ideology of abuse, 11 January 2023).

Instead of depending on restorative or transformative justice, Lee Shevek recommends that we look at anti-fascist tactics for ways forward. Most abusers, like fascists, are unlikely to change because they see their behaviour as justified and gain power from it. The focus should be on disrupting the abusers’ ability to abuse, freeing survivors, and recovering their autonomy.

An antifash hadith

Reading Lee Shevek reminded me of a conversation the messenger Muhammadﷺ had with his community, as documented in Al-Bukhari:

Muhammad (ﷺ) said, "Help your brother, whether he is an oppressor or he is an oppressed one." People asked, "O Allah's Messenger! It is all right to help him if he is oppressed, but how should we help him if he is an oppressor?" The Prophet (ﷺ) said, "By preventing him from oppressing others."

May what we learn inspire our actions to make it more and more impossible for our oppressors to dominate us. And may you experience relationships where you are free to grow, thrive, and feel love and respect for yourself, your kindred, your collaborators.

References channel

For notes and sources: are.na/liy/abuser-architecture