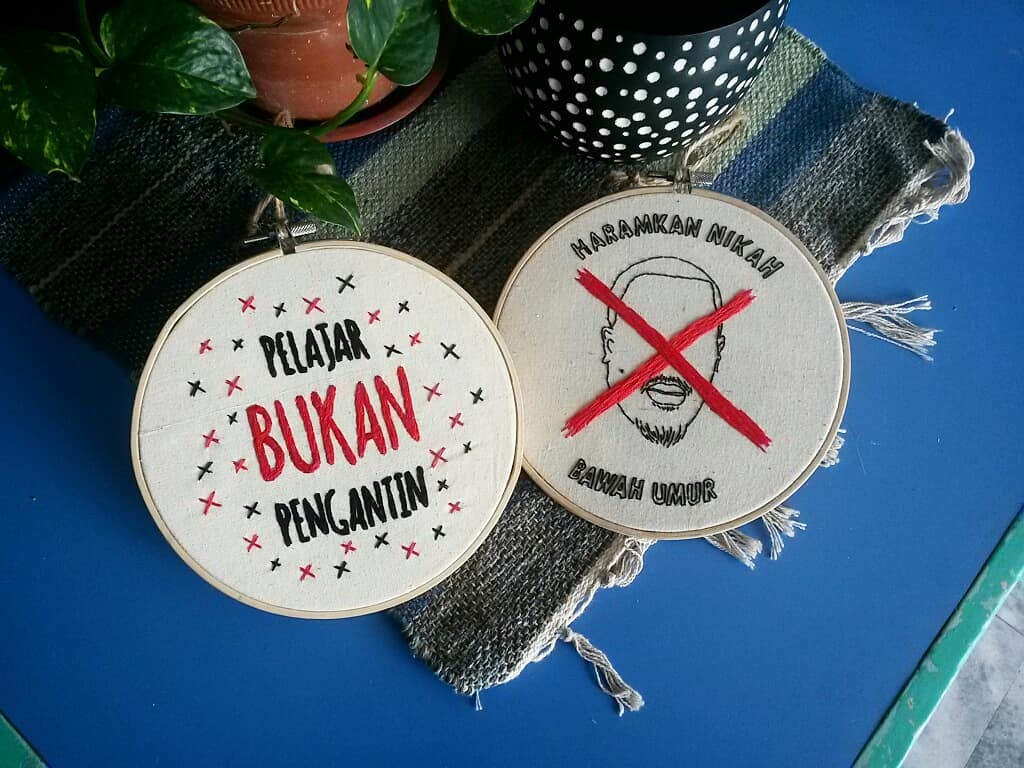

Against child marriage in Malaysia and Indonesia

Did you know child marriage is linked to ecological crisis? I share my notes after Indonesian and Malaysian Muslims at a public forum call for an end to child marriage.

- In 2017, a group of women ulama in Indonesia— former child brides among them— declared that it is wajib to prevent children from dangerous marriages.

- Such a congress centering women's authority was possible of a long history of women's involvement in religious spheres in Indonesia, where women's pesantren have existed since 1923.

- In 2010, Malaysia registered 82,000 child brides. This was an almost 40% increase in ten years. When confronted with advocacy on the social issue of child marriage, Malaysia removed public access to population census data about married children under the age of 15.

- In lieu of data transparency, women in Malaysia and Indonesia are speaking up— even in their 60s— about the trauma of being a child married to men 20-30 years older than they were.

- In Indonesia, child marriage is also commonly observed between two children. Underlying this narrative of child marriage is the feminisation of poverty and a lack of reproductive health education.

- A lens of substantive equality takes into consideration both biological and social implications of the affected. The overlooked social conditions of child marriage reflect the impact of patriarchal domination over classical texts on the lived realities of girls and women. Advocacy must bring this reality into sharp focus.

- Child marriage is observably correlated to ecological crisis. Child marriage has not ended poverty as intended, but rather extended it.

- Child marriage is an indicator that development ideology in Indonesia and Malaysia has failed. 73 years after colonial independence, Indonesia is ranked 7th highest in the world for child marriage.

- In 1984, Malaysia had some of the most progressive Muslim family laws in the world. Since then, development and political Islam pushed these rights to the margins. One of the five characteristics of political Islamists is to uphold child marriage as fundamental to their identity.

- Hadiths about Aisha cannot be the basis of law. Upholding child marriage creates a dangerous religious tension in both Indonesian and Malaysian courts.

- Child marriage fails our responsibilities to children and cannot be seen as a solution to other social problems.

- Malaysians can learn from the Indonesian approach to not limit their references to only the Qur'an, hadith, usul fiqh and scholarly opinions, but to also be informed by comparing laws, global conventions, and nature.

- As long as we hold to religious texts without connecting it to context or lived realities, we cannot achieve justice.

- It is the right of your child to access information about their bodies, reproductive organs, and sexuality.

- Child marriage is a corruption of the Muslim's responsibilities to the four Quranic pillars of marriage.

- The message we currently send to society is that a Muslim man can get away with anything. What can each of us do where we are to change that and end child marriage?

Against child marriage in Indonesia and Malaysia

by Liy Yusof after Kyai Jamal, Lies Marcoes, Nur Rofiah, Rozana Isa in 2018

1.

In 2017, a group of women ulama in Indonesia— former child brides among them— declared that it is wajib to prevent children from dangerous marriages.

The first Indonesian women ulama congress (KUPI) convened in 2017 to center women's truths in the production of fatwa, taking into account women's biological experiences, their stories of injustice, the state constitution, and scientific knowledge. They made the following declaration: Sexual violence is haram both inside and outside of marriage. Preventing children from any dangerous marriage is wajib, including child marriage. Protecting nature from any damage including environmental destruction in the name of development is wajib. Some of the women ulama of KUPI not only understood the texts very well, but had experienced child marriage themselves.

2.

Such a congress centering women's authority was possible of a long history of women's involvement in religious spheres in Indonesia, where women's pesantren have existed since 1923.

The congress saw 750 participants of both genders, academics, pesantren leaders, head of Muslim social organisations and allies from seven other countries. Indonesia itself has two large Muslim organisations, Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah, dating back to 1917 and 1946 respectively. Indonesia has a long institutional culture of pesantren, schools where people from all over the country enroll, relocate to live, and spend their time diving into classical religious texts. Women’s pesantren have existed since 1923. Women were educated as religious judges since 1950, and practicing since 1957. Nur Rofiah shared that there are also numerous NGOs based in women’s Islamic teachings, among which are: Rumah KitaB, Muslim Rahima, Fahmina, Alimat, and Puan Amal Hayati. There are also organised survivors who advocate for gender equality, such as Sahabat Ulama Perempuan.

3.

In 2010, Malaysia registered 82,000 child brides. This was an almost 40% increase in ten years.

In 2000, local census reports say almost 60,000 children and teenagers were already married (6,800 children under 15, 53,000 aged 15-19). Ten years later, about 82,000 Malaysian child brides are registered in 2010. In that same year, while going through the Ministry of Health reports to the UN, NGO workers at Sisters In Islam saw something strange in the data: Children as young as 10-14 years old were taking HIV tests— 445 of them in 2010, and a further 32 children under the age of 10. In Malaysia, HIV tests are a requirement for marriage. That was how the prevalence of child marriage in Malaysia caught the attention of the women's rights NGO.

When confronted with advocacy on the social issue of child marriage, Malaysia removed public access to population census data about married children under the age of 15.

The 2000 population census data made available the number of marriages for Malaysians under the age of 15, but after child marriage was highlighted as an issue, it was absent from annual census data since. Only data for marriages of 15-19 year olds were available for Sisters In Islam workers to use in their advocacy. I learned that Muslim marriage data is also only available at state level, not federal. NGOs and activists face a challenge compiling first-hand accounts of child brides. Not many are willing to come forward. Rozana Isa said we need more data from these lived realities to guide law and policymakers towards the end of child marriage. She implored that we critically question the quality and breadth of data available to us, and subsequently the quality of our decision-making without such data to guide us.

4.

In lieu of data transparency, women in Malaysia and Indonesia are speaking up— even in their 60s— about the trauma of being a child married to men 20-30 years older than they were.

The lives of these child brides are further complicated by the fact that their husbands are polygamists who are 20-30 years older than the children they married. Sisters in Islam shared a video interview with a child bride, now 60 years old, vividly recollecting the trauma and experience of being married as a child, including making two suicide attempts during the marriage. Rozana Isa said on the mental health of child brides:

"It is hard to imagine a child going through a complicated journey such as marriage at an age so young without any negotiating power or room to state her needs and desires, since she is already obligated through religious machinery to obey her husband. How can she defend herself against this pressure, even more so with mental health issues and depression? It was only thinking about her own children that gave her the will to live."

Rozana said perpetuating child marriage could increase the number of suicide attempts from mental health issues, increase the mortality rates of babies and young mothers, and increase post-partum depression.

5.

In Indonesia, child marriage is also commonly observed between two children. Underlying this narrative of child marriage is the feminisation of poverty and a lack of reproductive health education.

Lies Marcoes said what is necessary is research from the perspective of women’s empowerment, and open documentation of the gravity of the situation. At the event, she presented the work of Rumah KitaB, a foundation of researchers and network members in pesantren boarding schools across Indonesia. Child marriage is ritualised as a cultural norm in Lombok, Indonesia through the tradition of ‘kawin lari’, a form of ‘eloping’ girls as young as 13 into child brides. Indonesian law has changed over time from 21 being the legal age of marriage to the court legalising marriages of children as young as 13. Their parents commonly bring them to court concerned about zina. In Indonesia she says we often see child marriage between two children, unlike in Malaysia.

Child marriage is a layered and intersectional issue; Lies Marcoes likens it to a spiral, or a spiderweb. There are people involved in layers of law, society, and at national and global levels. Examples of this are a strong conservative Yemeni influence in Indonesia, as well as the feminisation of poverty that compels mothers to leave their homes to raise money for their children. 36 of 52 child brides (the oldest was 14) in a total of six territories told Rumah KitaB they married because they were pregnant, and so a lack of reproductive and sexual health education also becomes a key issue.

6.

A lens of substantive equality takes into consideration both biological and social implications of the affected. Advocacy must bring reality into sharp focus.

Nur Rofiah said that to practice substantive equality as a concept, we must take into consideration the biological and social implications of child marriage on girls and women. She pointed out that the biological consequences of a few minutes of male sexual activity can impact a woman biologically and socially from weeks to months to years. We can conclude that child marriage is dangerous for children because they would be expected to endure these biological consequences. Nur Rofiah illustrated the flow as such:

Advocacy ➡️ Reality ➡️ Religious Text ➡️ Substantive Equality ➡️ Advocacy

Substantive equality (kemaslahatan hakiki) needs to be differentiated from formal equality (kemaslahatan formal). Child marriage can perpetuate other social issues like violence, trafficking, access to education, employment and mortality rates. Advocacy must bring reality into sharp focus.

The overlooked social conditions of child marriage reflect the impact of patriarchal domination over classical texts on the lived realities of girls and women.

Nur Rofiah shared her research on the impact of classical texts on the lived realities of girls and women. Children are not asked for their opinions at all about their lives, and have no bargaining power over their most important events. Child marriage comes with the consequences of stigma: children are married off young for fear of zina or drawing zina to them, and girl children in particular are stigmatised as the source of family trouble. Daughters are subordinated and objectified as economic assets by parents and guardians who marry them off to repay debt. This reflects the larger societal devaluation of women merely as sites of reproduction. The child has to work while also being a young mother, enduring a sexual relationship, a full term of pregnancy, birthing an infant, raising her child while still being a child herself. When a husband tires of the wife because she can’t find work, is uneducated, or her biological function expires, the wives are divorced without their consent. The violence that these people face before and throughout their marriage permeates all realms: physical, economic, mental, sexual, spiritual and social.

7.

Child marriage is observably correlated to ecological crisis. Child marriage has not ended poverty as intended, but rather extended it.

Nur Rofiah said child marriage has not ended poverty as intended, but rather extended it. The root of the problem is the way girl children and daughters are perceived in their full humanity. Religion isn’t the only factor. As long as the dominant view of boys and girls are inherently different, child marriage can happen in developed countries, even modern ones. It is not a problem unique to Muslim communities either.

Lies Marcoes showed that the ten places in Indonesia where child marriage rates are the highest are also where ecological crises are most severe, with issues of industrialisation and loss of land impacting almost all of Kalimantan. To this I would also add: it is no coincidence that Sabah and Sarawak have the highest rates of child marriage in Malaysia.

8.

Child marriage is an indicator that development ideology in Indonesia and Malaysia has failed. Seven decades after colonial independence, Indonesia is ranked 7th highest in the world for number of child marriages.

Child marriage has been an issue even before Indonesia’s independence. 73 years later, Lies Marcoes observed that the problem is present and growing. It seems at odds with the practice of development ideology (pembangunan) in both Indonesia and Malaysia.

Theoretically, if development yields education, and education yields working opportunities, then the “promise of development” is that marriage as a whole becomes less urgent, let alone child marriage. Yet she concludes “development must have failed”, because 73 years into independence, Indonesia is ranked seventh highest in the world for child marriage. This is why reducing child marriage to a rural issue fails the full picture.

Lies Marcoes said: "There is a direct connection between child marriage and crises of economy and ecology. Our job is to reveal more data so the government can see this issue is not as closed as it appears. We show with a feminist perspective the relation between child marriage and all those issues. If there is no change in the economy, then the anticipated change is just theoretical. It is not even just a rural issue anymore. Now that the Islamist far right is growing stronger, we see even in cities child marriage practices start to take shape, and in very similar patterns to the rural pedalaman, since migration also carries tradition with it."

9.

In 1984, Malaysia had some of the most progressive Muslim family laws in the world. Since then, development and political Islam pushed these rights to the margins.

Rozana Isa on political Islam being the root of socioeconomic and legal issues: “When we achieved independence, our forefathers and mothers were on the right track in terms of developing our countries. Early laws and policies from the government of that time centered the marginalised in agriculture, fishery, and more. Along the way, the focus slowly shifted from development to fishing for votes. And this is where progress was compromised for populism, obstructing us from moving into a rights-based approach after focusing on development. Because of political Islam, these two have been compromised. Development is compromised, and the focus is now very much industrial. The marginalised are further marginalised. And although we have some progress in the public sphere, privately things haven’t moved as much. In fact, in some ways we have regressed. In 1984, Malaysia had the most progressive Muslim family laws in the whole world. Who are the government going to focus on now? Are Malaysians the center of the agenda, or are they worrying about the next four years, and thinking about elections all over again? As long as we are still figuring out what rights we even have, it’s going to be very tough.”

One of the five characteristics of political Islamists is to uphold child marriage as fundamental to their identity.

Lies Marcoes said of political Islamists: “Religion to this segment of community is their political identity and flag. To these people, child marriage is fundamental to their identity and they need to uphold it. They will also defend female genital mutilation (FGM) not as a choice, but as key to Muslim identity. They are also thirdly in support of polygamy, and will campaign extensively to preserve it. They are also anti-vaccine. And lastly, they are anti-LGBT and against recognition of sexual diversity in Islam. These five flags are what they are very proud of and need to be seen as aspects of their political identity.”

As for religious dalil commonly used to uphold the practice of child marriage, Kyai Jamal shared the following: recalling Prophet Muhammad’s marriage to Aisha, a conversation between the Prophet’s Companions Umar and Ali, the rights of ijbar in the social construct of Islamic fiqh, and fatwa from Saudi ulama. The discourse of child marriage in these perspectives is usually centered around puberty, zina and premarital pregnancies.

10.

Hadiths about Aisha cannot be the basis of law. Upholding child marriage creates a dangerous religious tension in both Indonesian and Malaysian courts.

Rozana also called out the abdication of power from the new ruling government in addressing child marriage issues in Malaysia. The same narratives used to justify child marriage are not challenged in the tensions between federal and state laws and uneven implementation. She called for accountability from the constitutional monarchy in their capacity as head of Islam in the country to address this issue directly.

Kyai Jamal said hadiths about Aisha’s child marriage cannot be the basis of hukum or law. Many ulama commonly find both the sanad and matan components of the hadith transmission problematic.

Lies Marcoes said although Indonesia does not have shariah courts except in Aceh, fiqh’s authority somehow supercedes law due to customary legal dualism. Judges tend to use religious arguments instead of legal ones. Rumah KitaB works with national organisations like Nahdlatul Ulama to educate judges on working through gender-aware perspectives with access to research and data. Since child marriage has a huge impact on youths, teenagers in Indonesia are now also speaking out openly against the practice.

In Malaysia, there are still discrepancies about the definition of ‘child’ at the federal level relating to the Child Act. In terms of legal issues, Rozana points out that regardless of the minimum age of marriage, girls under 18 can still be married off with the permission of Shariah court and ministry. “There is no bottom limit to this, and no standardisation right now to the reasons marriage can happen.” Without any standardisation in Malaysia to prevent child marriages from happening, survivors of sexual violence are often married off to avoid societal shame, especially if they are pregnant.

11.

Child marriage fails our responsibilities to children and cannot be seen as a solution to other social problems.

Marriage courses should not only emphasise the physical aspects of marriage. Dr Nur Rofiah asked: “Why do we assume of child marriage without zina, and zina without marriage? Why do we pretend the third option of neither zina nor marriage doesn’t exist? We need to shift the concept of purity and masculinity. What is important to me is to look at marriage course modules beyond fiqh. A focus on fiqh is so physical and makes marriage seem mostly about physical issues.”

Kyai Jamal said that it is hard to accept in fiqh that a sexual assault survivor must be forced to marry her rapist because he impregnated her. "Child marriage is a danger that cannot destroy another danger, and becomes a multiple burden instead." Instead of marrying the rapist at all, he said abortion is a solution: "Abortion has many opinions and no consensus within ulama— generally having one before 40 days is acceptable; some imams even say 120 days is still acceptable."

When it comes to deciding to marry a child to their abuser, Rozana Isa asks:

"Is that the basis of a marriage that will bring harmony and peace? We need to ask ourselves: Can that child be happy?"

12.

Malaysians can learn from the Indonesian approach to not limit their references to only the Qur'an, hadith, usul fiqh and scholarly opinions, but also be informed by comparing laws, global conventions, and nature.

There needs to be an urge to “match the text with reality,” Rozana says. Currently all discourse around child marriage begin and end at the seerah of the Prophet and do not take into consideration of usul fiqh, Maqasid Shari’ah, and comparing other methodologies.

One way forward is to advance the quality and diversity of religious discourse itself. Sisters In Islam is excited to make room for research and work coming from Indonesia, as well as Rumah KitaB’s publications on child marriage. The work of Rumah KitaB resists a textualist and fundamentalist conservative segment of society who campaign nonstop in directions that promote child marriage. For example, they campaign against dating, and therefore combine polygamy with child marriage as viable solutions to that problem. Campaigns like these receive support even in the University of Indonesia, where academics and jurists use Arabic semantics to conclude that “child marriage is aligned and appropriate in Islam.”

Since child marriage is an issue affecting both countries, she hopes to discover strategies and inspiration from the voices of Indonesian ulama that center women’s rights. Rozana Isa admired their approach to not limit their references to just the Qur’an, hadith, usul fiqh and opinions of major ulama, but that they also look at laws, state philosophy, and honour global conventions. She also found it inspiring that they draw from nature to inform their opinions as well, and felt Malaysians have a lot to learn from their approach.

13.

As long as we hold to religious texts without connecting it to context or lived realities, we cannot achieve justice.

Rozana on addressing injustice of child marriage holistically:

"As long as we hold to the religious texts without connecting it to context or lived realities, then justice will not be achieved. I still call for lived realities to surface. We need to look at our experiences so that we can make a fair assessment. We must create data— and not just from age of marriage, but health, career, decision-making— to first analyse the impact of child marriage, before we can talk about laws and policy."

She also pointed out the importance of meaningful involvement from different segments of society, including stateless communities, migrants, and refugees.

14.

It is the right of your child to access information about their bodies, reproductive organs, and sexuality.

Lies Marcoes on education as a form of harm reduction:

“Not to hide information about your body, your sexuality, your reproductive organs. It is the right of your child to have that information accessible to them. It won’t lead them astray necessarily, but without it they will definitely go astray. Give them information, respect their decision, and work with it. As religious dalil say, ‘mudarat jangan dijawab dengan mudarat lagi’— this is my justification for harm reduction.”

Lies Marcoes said there is already precedent for this in Indonesia's pesantren:

“In madrasah pesantren, there are lessons about purification, that is the first part in a kitab by Dr Harun. We need to be very open, to create opportunities to talk about anatomy. We might not directly call it reproductive health or sexual education. We just talk about it in terms of education about purification. In certain kitabs these get more detailed over time. So it is untrue to say publicly this discourse is prohibited, because through these kitabs are already some explanations or opportunities to discuss sexuality at every turn.”

Rozana Isa said it is our responsibility to respond to questions that children have about their bodies, so they can develop healthy boundaries:

“We also need to look at what happens in today’s society, and all the cases of sexual violence towards children. We are not given information about our bodies and anatomy with the right terminology. The problem an educator faces when discussing child sexual violence— the mothers she meet might say instead of “alat sulit vagina” they would say “flower” for girls or “bird” for boys. So when a child goes through something and tries to communicate it, she might use the term “flower”, and it does not occur to the parent that this is indicative of a more serious problem. To social workers like these, terminology is important, because we do not name the anatomy out loud and therefore lack the consciousness to understand when wrongdoing has been done. They can’t say “He touched my butt” or “he touched my vagina.” We have to empower our children to say it like it is. We also need to realise our children are more exposed to social media and family, and are very observant. My 9 year old for example is already asking me what periods are. I have a responsibility to tell her, instead of saying “You don’t have to think about this till you’re 12.” If she already has the curiosity and knows this is something that will happen to her, I have the responsibility to tell her. Other issues so they understand the human body, and what is a good touch and what is a bad touch. Who can touch you and where can they touch you. So they understand that not only does she need to respect herself but others need to respect her and her boundaries too. And other people must treat her with respect.”

15.

Child marriage is a corruption of the Muslim's responsibilities to the four Quranic pillars of marriage.

Because people are spiritual beings, the purpose of marriage is also to cultivate spiritual peace (sakinah). Sakinah is predated by mawaddah wa rahmah, which means a mutual reciprocity that yields substantive equality. Only with a love like that can a family be one of sakinah.

Nur Rofiah shared the following four pillars of marriage in Islam informed by the Qur'an:

- Conviction that they are each other’s partners (zawj in 2:187)

- Upholding the union as a promise (mitsaqan ghalizhan) (4:21)

- Mutually upholding dignity of their partner (4:19) (mu’asyaroh bil-ma’ruf)

- Mutually solving problems through discussions (2:228, 3:159)

Considering these pillars alongside the phenomenon of child marriage, we are led to conclude that child marriage is incapable of maintaining these pillars of marriage, and therefore preventing child marriage is a wajib act.

16.

The message we currently send to society is that a Malay Muslim man can get away with anything. What can each of us do where we are to change that and end child marriage?

Rozana reminded the room that everyone has the responsibility and obligation to do what is best for all Malaysians.

"When it comes to minimum age of marriage, the Qur'an is silent. It doesn't advocate for any minimum age, which means it is entirely on our wisdom to set the best for its people. It’s within the government’s power to do this. And we have to hold them accountable in caring for its people."

Rozana Isa:

“As long as the narrative doesn’t shift to a woman has complete agency to decide for themselves what is best for her— that she is her priority, not men, boyfriends, or future husbands— the conflict will remain. The moment she enters a relationship the conflict is there to be easily manipulated, and it is easier then for women to do something they don’t want to do. We also do not hold men accountable enough to respect women. We are not demanding this enough from our Malay Muslim men in Malaysia. Not enough! The message we send to society is that a Malay Muslim man can get away with anything.”

Rozana Isa implored that we start normalising the awareness of child marriage and resist the rhetoric that supports it with our family, friends, and communities.

"I hope the people in this room feel some sense of responsibility to the change we want to see."

What can each of us to do end child marriage in our countries?

Documented by Liy Yusof, 31. This is what I learned from Indonesian and Malaysian Muslims at an all-day public forum in 2018 as part a campaign to end child marriage, Pelajar Bukan Pengantin. I appreciate the learned panelists from Indonesia and Malaysia for sharing their knowledge: Dr Nur Rofiah, Lies Marcoes, Kyai Jamal, Rozana Isa, and moderator Melissa Akhir. When I quote them here, I've translated their words into English unless they spoke it directly. I hope I represented their ideas accurately, and if I did not, the fault is my own. The forum was held in Kuala Lumpur, October 2018 by Sisters In Islam, a nonprofit organisation advancing women’s equality, justice, freedom and dignity.

You may also be interested in: