Here is a queer Muslim wellbeing workbook to help you feel less alone

Sheltering indoors in the holy month of the first year of the global pandemic, encouraged by a friend, I made a love letter to God and to all the queer Muslims who changed my life.

Feedback from the voices in this project

- “This made me think a lot about so many things I never thought of before.”

- “Thank you for providing this opportunity for queer Muslims to see we are not alone.”

- “Answering the questions was very emotional for me.”

- “Thank you for doing this. May Allah reward and guide us to the life we want.”

- “I think this project will help LGBT Muslims immensely.”

- “I can’t even imagine this project but thank you for having me be a part of it. This is going to be very cool and wonderful. May we keep doing beautiful things.”

- “I really think religious queer Muslim spaces are important. I find much of queer Muslim organising is secular, and it’s frustrating. Sometimes I would prefer organising an interfaith queer space, because the God-consciousness is important to me above all. Thanks for doing this work.”

- “Love this exercise. The experience of answering was like a spiritual journey. Thank you for the thoughtfulness in your questions.”

- “Thank you so much for compiling my story. I hope my sharing helps give perspectives for others out there. God bless you.”

- “I send love and peace to all.”

- “Thank you, this was healing. May Allah bless you and your loved ones.”

- “This is so dope! I’m saving my answers because reading them reminded me of the blessings I forgot I had.”

- “Answering this makes me so incredibly happy. Thank you for asking questions that matter with such poise and tact. May all your proceedings go well, inshaAllah ameen.”

- “It was a nostalgic experience. In a good way, it brought back memories of those years and reinforced the importance of doing more for others.”

- “It’s really been a pleasure doing this! I think this is a beautiful project.”

- “This project is really important. I’ve felt alone for a very long time. Everyone is going through their own journey, and I don’t want to burden others with mine. But I can’t do this on my own. I can’t do this on my own.”

WELCOME

Notes from the writer on the process, and from the artist on design terms of use

WRITER'S NOTE

Hi, I'm Liy!

If you're reading this, then the wild beautiful idea that found words for itself while I was in a park sometime late 2019 is finally alive: A love letter to God, to all the queer Muslims who changed my life in years of navigating human rights spaces, and to the ones I haven't met but I know are out there.

The sub-title and theme of this book comes from a post-it of mine that has stared back at me for two years: “Queer Muslim courage?” Like it was waiting for an answer. As I witness our resilience to find and make pockets of warmth away from pain, what comes up again and again for me is the idea of being a queer Muslim ancestor: What if we could approach queer Muslim collective care as being part of a whole generation that doesn’t want the next to feel they’re starting on empty like we did?

I also didn’t think I had queer Muslim elders until my 30s. I didn’t know who to turn to. What if we see it as care for the queer elders we’ll become, and trying our best to see as many of us get there?

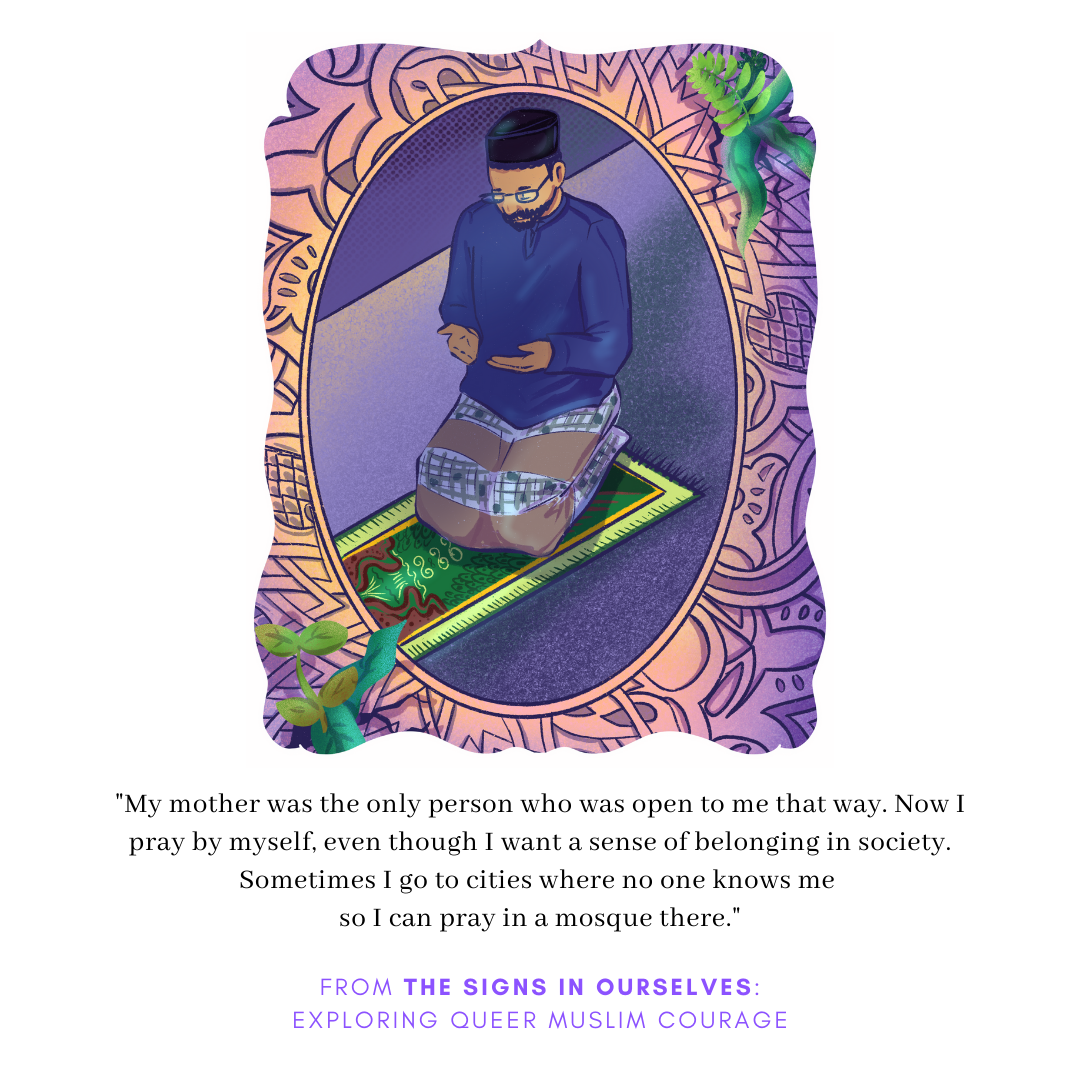

Activism and allyship around queer/LGBT Muslim rights can only do so much if we inherently believe our identities exempt us from Divine love. Instead of expending energy countering what others say about us, we need to build our spirituality as a collective and reclaim access to (and authority of) the Divine.

Our journeys have signs for all to learn from in explorations of compassion, faith, and identity. It was important to me to make a project about the strength to not let others kick us out of our faith while we heal from the trauma attached to it together. I saw an opportunity for an affirming wellbeing resource that could be just as useful downloaded to your bedroom or disseminated in a workshop anywhere in the world. This is a humble offering in that direction, and an excuse for me to talk about God with Muslims I relate to.

NOTES ON METHODOLOGY

- There was two criteria for everyone's participation: firstly, that they identify as Muslim by choice even if made to feel ‘not Muslim enough’ by others; secondly, that they do not identify as a cisgender heterosexual person.

- The conversations took place in a mix of English, Bahasa Melayu, and Bahasa Indonesia, and are presented here in English. I spoke with each of them for a few hours online in the first year of the global pandemic and wrote all the way through the holy month.

- Besides the dozen or so people I spoke to, you’ll also find brief answers from LGBT/queer people who self-identified with the participation criteria. They submitted their own answers to the interview questions online — a survey link was disseminated across a few networks, and we collected answers from 14 countries. Their responses anonymously accompany the Southeast Asian stories along with prompts for you to do the same, whether alone or with trusted people.In the interest of representing diversity in anonymity, each response is tagged with any two of the following identifiers: Age, gender, sexual orientation, location, and job. Their pronouns are also included so you can refer to them in collective discussion.

- I preserve the names and pronouns people choose for Allah as much as possible, including the gender-neutral ‘Dia’ in Bahasa Melayu and Bahasa Indonesia. The voices in this project refer to themselves as ‘LGBT Muslims’, ‘queer Muslims’, and more. I also refer to them as ‘sexually diverse Muslims', building on the idea that human diversity is just another form of divinely granted biodiversity. In my opinion at the time of writing, the term also easily includes people who are intersex, asexual, neurodivergent and more.

- Non-English words are not italicised. Italicising is a practice typically indicating a word is foreign, when the reality is that everyone who is a part of this project speaks at least 2-3 languages and English is often the most foreign of them all. With well over a billion Muslims around the world, I consider that listing the 14 countries of the anonymised voices in this project does not do much to express the complexities of migration, sociopolitics, and race we face in Muslim-majority and minority contexts. I thought it would be interesting to instead share the non-English languages of the voices in this project, considering everyone in it is at minimum bilingual:

- I prepared essay sidebars with information and tools to accompany what emerged. We feature some work from South Asian scholar Dr Ghazala Anwar and also Dr amina wadud, a specialist in textual analysis from a gender and sexuality inclusive perspective. Although the voices in this project skew to Southeast Asia, we believe it’s important to listen to South Asian and Black Muslim voices who incorporate gender and inclusivity in their praxis.

- The youngest of us in this project is 15, and the oldest is in their 60s. Some of us were born into Muslim life, and some embraced Islam along the way. You’ll find stories from divorced mothers, Islamic studies scholars, and former atheists, among others. Some of us have been in loving relationships for over a decade, others have yet to encounter their first. I tried my best to hold their truth with care, and am excited to share their stories with you.

- Remember that the core of the project is storytelling from people who want to be heard. Above all, this resource is a humble collection of real stories to help you feel less alone and imagine ways forward in your own journey. I hope you remind yourself that each story may take minutes to read, but took years to live out.

ARTIST'S NOTE

written by Dhiyanah Hassan. Liy has edited this to reflect the online series adaptation. For the original version, download the fully-illustrated pdf here.

ON ART AND DESIGN

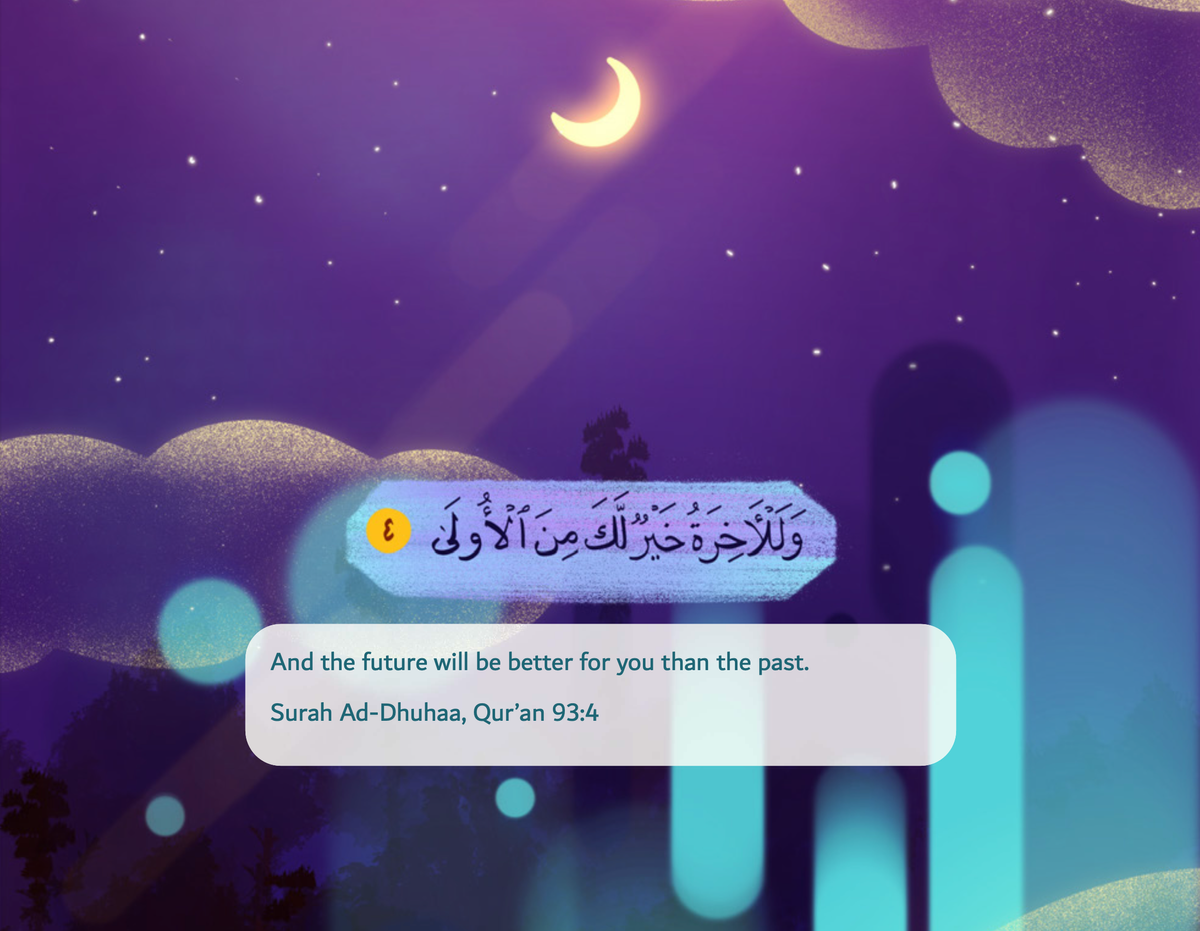

Every visual element you see in this series was digitally hand-drawn, including batik motifs, Qur'anic scripts featured in artwork, and patterns. Some elements have been inspired by references shared by participants of this project while others were derived from my research and personal explorations as a queer Muslim South and Southeast Asian artist. All portraits featured are intuitively imagined to maintain anonymity. The visual theme for this book echoes the Islamic five-times-a-day prayer ritual, signaling the Sun's movement through the sky. Each prayer time is expressed through the frames' colours and patterns on each page as the text flows like a river through them. Throughout the book, you'll find visual portals, echoes, and cues in the form of small and large illustrations that accompany the voices here.

TERMS OF USE

You may share and interact with the artwork for personal use only. You may engage with the art for personal viewing (eg. as wallpapers for personal devices) and as inspiration and creative references for your personal and communal interactions with the exercises in this book. However, no aspect of the art or design element— in whole or in part— should be exhibited, manipulated, recreated, or redistributed for use in any materials for sale or commercial purposes.

Any sharing of the artwork in print and online should be properly credited back to the artist and this book (for example: Artwork by Dhiyanah Hassan, from The Signs In Ourselves: Exploring Queer Muslim Courage by Liy Yusof).

While you are encouraged to get creative with how you hold space for this content, these boundaries are here to support us in articulating, honouring, and respecting the creative and communal labour that went into the creation and publication of this wellbeing resource.

The Signs In Ourselves

This post is part of a series of stories exploring queer Muslim courage.

Read all posts🧿 Welcome

You are here!

🧿 Our Environments of Truth

🧿 Exploring Divine Presence

🧿 Learning from Time and Each Other

This is adapted from The Signs In Ourselves (pp. 1-7), a queer spiritual wellbeing workbook inspired by Qur'an verses 41:53, 51:20-21, and interviews with Southeast Asian Muslims. Written by Liy Yusof and illustrated by Dhiyanah Hassan, it was made available online in 2020 by the Coalition for Sexual & Bodily Rights in Muslim Societies. May Allahﷻ accept this offering and bring it to those who need it. Letters and inquiries: qmcourage [at] gmail [dot] com.