Writing for insight: Some design principles

How did I take notes before? What did I learn about writing for insight? How do I know what I know? Written at the 5-year mark of my zettelkasten practice.

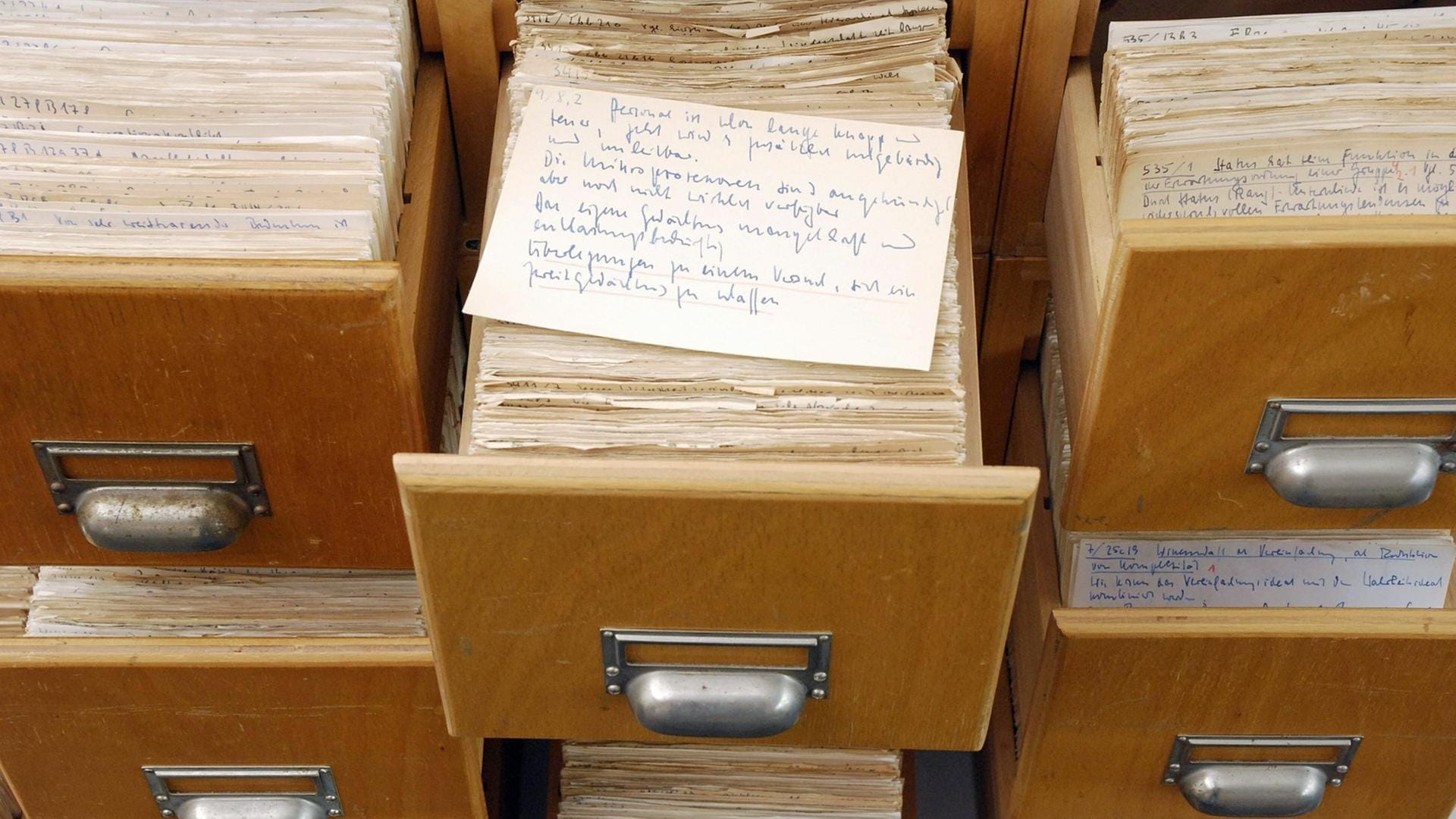

I started building and practicing my notes system in 2019. Just as I was feeling that I would never be able to catch up to the large amount of words I had left for myself to find, I came across the work of a German sociologist who wrote 70 books and 400 articles in his lifetime. He didn't exactly start early either. Even more intriguingly, when asked about his process, Niklas Luhmann said writing all that was easy for him, because all he was doing was engaging with his slipbox of notes (zettelkasten in German). This was before anything digital, so his note taking system was a large box of handwritten index cards that he would add to and connect between each other in different ways. He credited his notes system for much of his ability to write. When people ask about my notes system, I usually recommend they read Sönke Ahrens, How to Take Smart Notes: One Simple Technique to Boost Writing, Learning and Thinking. I read it back in 2019 but now there's a 2022 second edition. Much of the ideas in this post were first distilled from that book as practice— they were the first notes I ever put into my system— and they are seasoned from five years of tinkering (thinkering!). Ahrens also writes about Luhmann of course, but it's no substitute for going down your own zettelkasten rabbithole (see the end of this post).

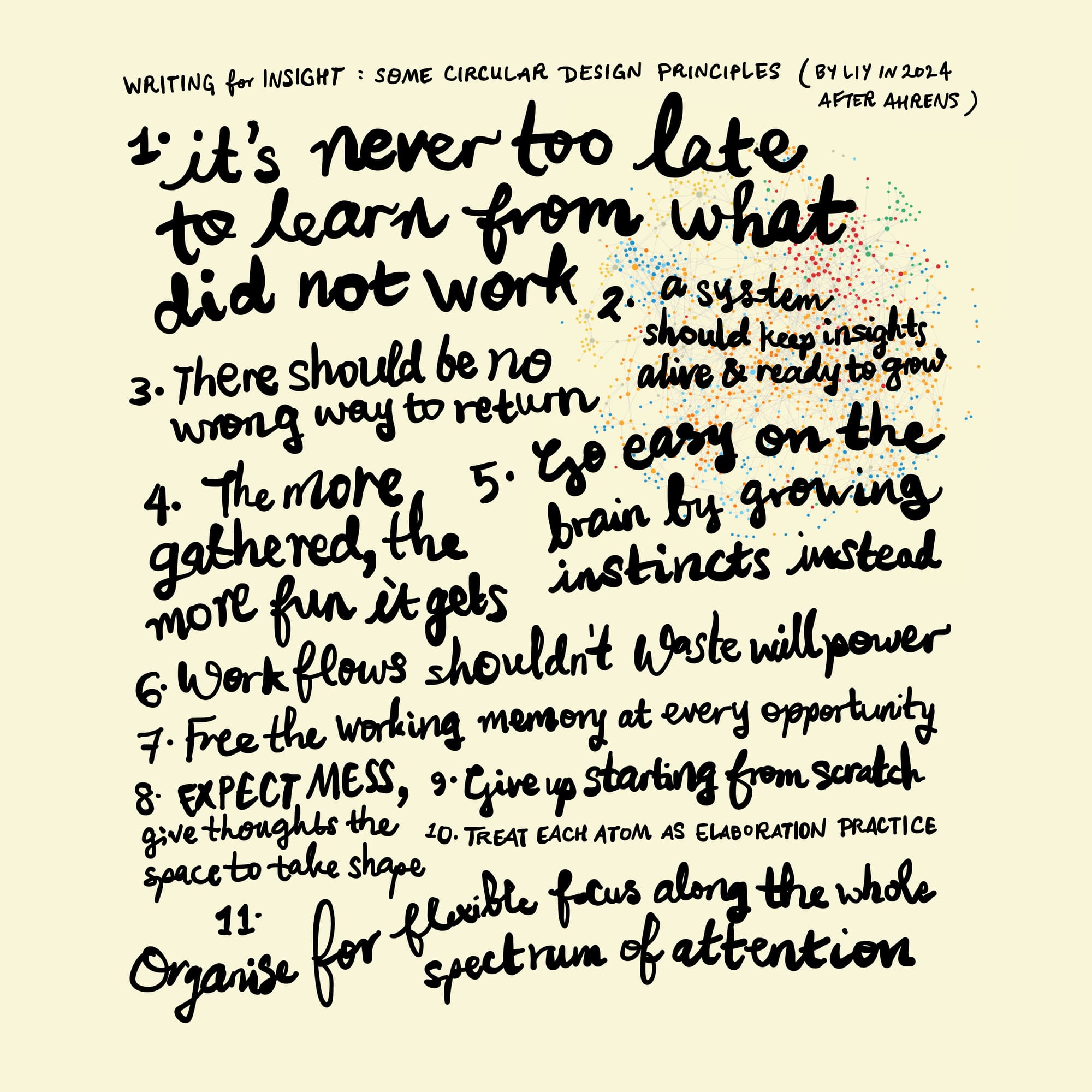

Writing for insight: Some circular design principles

- It's never too late to learn from what did not work.

- A system should keep insights alive and ready to grow.

- There should be no wrong way to return.

- The more gathered, the more fun it gets.

- Go easy on the brain by growing instincts instead.

- Workflows should not waste willpower.

- Free the working memory at every opportunity.

- Expect mess, give thoughts the space to take shape.

- Give up starting from scratch.

- Treat every atom of thought as elaboration practice.

- Organise for flexible focus along the whole spectrum of attention.

ARRIVAL

1. It's never too late to learn from what did not work

I left sticky notes on surfaces around the home. I carried notebooks around until I forgot where they were and/or some significant event led me to start a new one. I amassed boxes of paper journals that, at best, grew dust until I remembered them, and at worst, disappeared and reappeared in distressing ways. I tried punching holes in my notes and filing them into colour-coded sections. I filled up task apps with notes and notes apps with tasks. I tried Evernote but got overwhelmed by the amount of notebooks and notes I created. I tried organising with the PARA method. I was an early adopter of Day One, even digitising over 20 years of journal entries dating back to 1999, but eventually like many other apps it shifted to a subscription model. I tried organising my thoughts rather beautifully in Notion, but it only lasted as long as I could keep coming back regularly enough— if I broke the routine, I would be compelled to redesign from scratch just to be able to pay attention and use it consistently again. I haven't used any of these in years now. There's no point in having great apps or tools if they don't fit together in a coherent working process. I also learned more about digital security along the way, which changed my perspective on data ownership.

2. A system should keep insights alive and ready to grow

Although I barely managed to earn a university degree, it was clear that I have never stopped writing down the things I learn, and probably never will for the rest of my life. If I didn't figure out how to manage this, I would only overwhelm myself as I got older. I was frustrated knowing how much was sitting in all these pages and chronologically-arranged entries that I could play with and re-combine in so many ways, yet couldn't find any specific thing I was looking for. And so I walked around feeling like I could have been writing more than I really was— or doing more, even. I had generated a lot of text, but retrieving it when I needed it wasn't always easy or possible. I also realised I was confusing something within the process, though I couldn't articulate it at the time. There was a mismatch between the tools I used and my needs. The right system for me would help me cultivate and play with ideas so they don't slip away. I needed a system to keep insights alive— even ideas I disagreed with— for life-long learning. Writing alone wasn't enough. Without a way to organise or retrieve what I wrote, I was losing track of ideas that could have helped me grow. I didn't need a tool just to store text, organising it for the future is how I can continue to build on and reuse my ideas.

ARTICULATING MY NEEDS

3. There should be no wrong way to return

I should be able to wander into the system at any point and re-enter an older conversation without feeling lost. If it is too complex right away, I tend to abandon it because I do not know how to come back in the same 'way' I did when I was building it. A good system should have me feeling like I can take a break. Breaks are more than just recovery, they're part of learning. We know now that rest helps the brain process information and move it to long-term memory. So even if I am feeling eager to skip a break and push through, I know it's much better for learning and thinking to have a walk or a nap. Returning to a system shouldn't feel like re-tracing my steps in a maze, it should feel natural and open no matter how much time has passed.

4. The more gathered, the more fun it gets

Gathering knowledge into the system should feel playful, not more overwhelming over time. It shouldn't be harder to find older notes as new ones arrive. In many top-down or first-order note systems, the more notes I made, the harder it got to retrieve the right ones and relate them playfully. Whether I'm writing ideas in a notebook (diluting good ideas and making retrieval a hunt through time), collecting notes only by projects (limiting my ideas to project timelines), or generating unprocessed temporary notes (pure chaos)— in ALL cases, the benefits of note-taking decreased as the number of notes grew. Sorting by topic or hierarchical taxonomy puts too much responsibility on my brain to remember where and when similar notes were written down. A system that grows well makes gathering ideas feel easier and exciting over time.

5. Go easy on the brain by growing instincts instead

Relying on my brain to remember where and when notes were written just doesn't work. How we organise everyday information affects both short- and long-term memory. When I used to organise notes into folders by topic, it got messier over time because a top-down taxonomy made it harder for me to build connections across notes. Instead of imposing a structure from the top-down, the structure should emerge organically. A good system should help me feel lighter over time, reduce the burden on my brain, and help me flow easily into what I am already thinking about. 'Instinct' is a history of experience feedback loops. Instinct grows when we rely on layers and cycles of embodied experiences, practice, and understanding. Everything I practice prepares me for moments when I won't have time to deeply consider my actions. Trusting in my system means my brain can let go and stay present. The more I trust the system, the more I trust my instincts elsewhere.

SOME CIRCULAR DESIGN PRINCIPLES

6. Workflows should not waste willpower

Organise research and writing around reducing the number of decisions you have to make overall. Motivation is a muscle, and willpower is a limited resource that runs out quickly and needs time to recover. Acts of volition (like deciding how to add every new piece of information as it comes) are too tiring to be spent on maintaining the system itself. We could be using that mental energy elsewhere. So go easy on the brain by removing complexity, guesswork, and decision-making wherever you can in maintaining the system. The easiest way to start is to treat each note added to the system in the same way. Ahrens gives the example of shipping containers and how they are labelled and handled the same way regardless of what they hold. Practicing a common notes template allows a critical mass to build up without being overwhelming, and it saves us from navigating inconsistencies as a collection grows.

7. Free the working memory at every opportunity

Standardising workflows to reduce the number of decisions we have to make saves willpower, attention, and concentration. Our working memory is a limited resource; apparently, most of us can hold about 7 things in our head at once until they're forgotten, replaced, or moved to long-term memory. Did you know the brain can't tell the difference between a task that's done and a task postponed with a note? Writing something down can get it out of our brains, freeing us up to focus. So delegating thoughts to an external system preserves the capacity of our working memory. A good system should allow for quickly gathering these ideas without friction or demanding immediate attention.

8. Expect mess, give thoughts the space to take shape

Task management systems are often used to collect everything in one place and process it systematically, even more so after David Allen's Getting Things Done (GTD) principle took off in the early 2000s. The principle is known to many knowledge workers for a good reason, says Ahrens: because it works. GTD does help free short-term memory and maintain a clear structure for daily work. However, writing for insight is not a linear process. "Writing a page" actually means many tasks that can take minutes or months. GTD's style of concrete steps and clearly-defined objectives don't fit with the messy process of writing, where Ahrens says "one has to navigate mostly by sight." Insightful writing needs flexibility. A good system should be organised openly enough to hold vague ideas as they shift and become clearer over time.

9. Give up starting from scratch, instead build gradual and systematic exposure to feedback loops

Brainstorming from a blank canvas is not where most ideas come from! We tend to begin with what we already believe. Our thoughts are shaped by what we have known and experienced. All interpretation is a circular process: what we understand from before influences future questions we ask, and future questions we ask influences our understanding from before. The fancy word for that is a hermeneutic circle.[1] That circular process is what practicing a good notes system should feel like: to never 'start from scratch' again.

10. Treat every atom of thought as elaboration practice

By now we've considered designing a common notes template to practice (6.) so notes can be added to the system without being slowed down by its maintenance (7.). We've differentiated this thinking+writing+learning process from the neatly-planned tasks of project management (8.) and brainstorming from scratch (9.). The notes system takes care of distracting details and references, and is a long-term memory that holds thoughts as they take shape. This means we now have our best energy to spare on adding notes to the system! This is a practice of elaboration. What that looks like is spending a bit of time after absorbing new information to say it back in your own words AND connect it to what you already know. This is what differentiates elaboration from learning isolated facts or trivia. Elaboration is where we can really think about the meaning of that atom before it forms molecules with others: How would you remind yourself of [that thing you saw/read/heard] years from now, or elaborate to someone else over tea? How could it inform other topics and questions? How can it be combined with something else that you know? When each note is a brief atom of thought that I brewed in my own words, I can re-encounter it at any time and know it's ready to go. A good system means one will have been writing all along, instead of all at once.[2]

11. Organise for flexible focus along the whole spectrum of attention

Arguments, topics, new questions will emerge organically when you focus on what is relevant and interesting. Let's think of this focus as flexible instead of a more relentless type. Writing for insight requires a playful use of the whole spectrum of attention, because what we call "writing" is actually a bunch of tasks that require different types of attention, for example: outlining focuses on the whole argument; drafting or assembling thoughts needs associative and playful attention; reading needs either careful or skimming attention; proofreading asks that we dispassionately block out knowledge to see what was written. We need to be able to apply focused and floating kinds of attention in both science and creative work. Successful problem solvers have flexible focus in common, not relentless focus. Switching between roles well requires clear separation between tasks and becomes easier with experience. An experienced writer focuses on one role at a time in the process instead of being a slow perfectionist.[3]

'hermeneutic' comes from Greek hermeneutikos "of/for interpreting", hermeneutes "interpreter." Also linked to the Olympian Hermes, deity of speech, writing, eloquence. ↩︎

You also become more open to new ideas the more familiar you are with ideas you already encountered. Ahren cites Rheinberger (1997) when he says without intense elaboration, it would be hard to see the limitations of an idea we encounter in the wild. He also writes: "If open-mindedness is all that is needed, the best artists and scientists were hobbyists. Jeremy Dean, who has written extensively on routines and rituals and suggests seeing old ways of thinking as thinking routines, puts it well when he writes that we cannot break with a certain way of thinking if we are not even aware that it is a certain way of thinking (Dean, 2013)." ↩︎

To be able to switch between critic and writer roles requires a clear separation between these two tasks which becomes easier over time with experience. Ahrens: "Letting the inner critic interfere with the author isn’t helpful, either. Here we have to focus our attention on our thoughts. If the critic constantly and prematurely interferes whenever a sentence isn’t perfect yet, we would never get anything on paper. We need to get our thoughts on paper first and improve them there, where we can look at them. Especially complex ideas are difficult to turn into a linear text in the head alone. If we try to please the critical reader instantly, our workflow would come to a standstill. We tend to call extremely slow writers, who always try to write as if for print, perfectionists. Even though it sounds like praise for extreme professionalism, it is not: A real professional would wait until it was time for proofreading, so he or she can focus on one thing at a time. While proofreading requires more focused attention, finding the right words during writing requires much more floating attention." ↩︎

CAVEAT ON AHRENS

So if you get into the Ahrens book, you'll see he does explain Niklas Luhmann's zettelkasten system. But I personally found his explanations a bit confusing— the greatest value I got out of his book is the frame of mind that lead to this post. Thankfully, Luhmann's entire index card system has been scanned, studied, and scrutinised online in both German and English long after he passed. So whenever Ahrens confuses you, it will be useful to look up what Luhmann fans have left behind for you to find. As someone who went trawling in both languages, I would advise that you don't fall too deep into the fandom or follow it to the letter; his index card system was designed in an analogue time, and digitally we now have things we can use to our advantage to adapt, like a search feature and hashtags. So look Luhmann's zettelkasten up, but don't get swallowed into the structure; focus on practicing these principles in small batches with what you already have, so that you can find something when you need to. Getting that right is what took me the longest time in these past years.

In my case, I also didn't resonate with the Ahrens typology, like his choice to use the names 'permanent' and 'literature' for note categories left me stuck for awhile about what they really were. Going back to Luhmann cleared this up for me immediately: he used the words zweitgedächtnis (literally second memory) and lesegedächtnis (reading memory), and so I now think of it as reading and second memory too— marking with emoji 🔹 notes that are facts, events, reports and 🔸 for notes that are concepts, claims, ideas that I may or may not agree with but want to remember. For a description of my notes system, see:

When Luhmann was questioned about how prolific he was after taking on his notes system, his answer was basically "oh, like it's hard???" and it felt very smart-person nonsense to me at first. But five years in, I understand that energy a bit more. My anchor is dyslexic and started his notes system with the same principles at the same time; it looks very different from mine, and in 2024 he’s reading and writing more than he has ever done before. Whenever I have free time and people ask me what I plan to do, and I say "hang out with my notes," it isn't some agonising ordeal. I don't think I could spend enough time in my system. I want to grow it and think from it all the time. I don't know if I am getting better at it, but I do get what he means that writing feels easy. I don't have to 'come up' with anything anymore. These days, the longest part of the process is cutting things down, keeping it simple, to decide to stop at this point and just hit Done, because one thing always connects to another. I could always keep going.

Reference channel

see: are.na/liy/writing-for-insight-design-principles